Back to the Cave

This talk was given on September 11, 2016 as the closing keynote of XOXO Festival, a conference for independent artists on the internet. Thanks to Andy Baio for the invitation to speak.

Hi, my name’s Frank. I’m a designer, writer, and illustrator. But none of that matters today. I’m up here speaking because I’m like all of you: I need to make things.

Need is the right word, I think: if I go too long without some sketchbook time, I shrivel up like a house plant that hasn’t been watered in a few days. Maybe you’re the same. Making things is a necessary way of being in the world for people like us and an important tool we use to make sense of everything. All of us tap into this kind of creativity, but only a few of us have developed such a dependency on it.

I call that need the creative hunger. People either intimately understand this craving or they think it’s weird to put so much of an emphasis on it. Hunger? Really? And I know. It’s a little heart-clutching, like something you’d roll your eyes at after reading in a poem. This need is hard to explain without being too precious. I believe we all have it, but until recently, I didn’t have a nice way to explain it so we could see it in ourselves. But then I got a little gift—a lot of my friends had kids.

You know kids: going places they don’t belong, finding things they shouldn’t, then taking those things and immediately putting them in their mouth. On one hand: yeah, gross—drool, germs, etc. But on the other, infants and toddlers put stuff in their mouth to better understand it. Everything is new, so they must use all of their senses. After a little Wikipedia time, I learned infants mouth things to sooth themselves and develop the motor coordination in their mouths that are necessary to speak.

So now I have a new way to explain the compulsion to make things.

Making things is putting the world in your mouth.

I make things for the same reasons babies put things in their mouths: to better understand the world, to sooth ourselves, and learn what to say.

This also describes many of you, whether you draw comics, take photographs, make music, write code, or anything else. We’re all of a similar kind—a community of people bound together and driven by this other hunger.

So… How big is this club? How many in the world and how many ever? And how long has this hunger been around? I went looking for that answer, and wound up at another mouth: the mouth of a cave.

This is the Cave of El Castillo in the north of Spain. Take a few steps into that hole right there, and you’ll find this:

Yep, a handprint. It doesn’t look like much, but it’s the start of it all. Radioactive dating tells us the handprint is almost 41,000-years-old, the oldest art on record. This is the mother of creation, or at least her hand. The first artist was a woman, and we can tell by the relative length of her fingers. Forty-one millenia ago, a woman put some ochre into a hollow bone and blew the pigment around the outline of her hand. We found her mark 1,600 generations later.

It is impossible to know why she left her handprint in the cave. Was it to leave a message? From a belief in magic? To find her way out of a dark place? We can only guess. But it is also difficult to understand why we choose to make the things we do.

Do yourself a favor: think about the last personally significant thing you made. Why did you do it? To leave a message? From a belief in magic? To find your way out of a dark place? How much has changed in 41,000 years?

One thing persists: making things is hard. We all know the frustration and confusion of getting an idea out of your head, never mind the vulnerability of sharing it with other people. It’s fitting that art would be born in a mysterious and hidden place like a cave, because creativity and caves force you to navigate in the dark. You go by feel with unsteady footing. You run your fingers along whatever is within reach and take it one slow step at a time. It’s only after you’re out of the dark that the choices seem inevitable.

I attended the first XOXO in 2013 and remember being surprised by the bittersweetness of most of the talks. You’d expect to hear cheerier perspectives from such accomplished people, but the tone made sense. Independence and creativity are not all sunshine, and putting the two together is doubly not all sunshine. I was having a rough time in 2013, so I really appreciated and identified with hearing some honest talk about the struggles independent creative professionals face each day.

They told the truth. Independence gives control, equity, transparency, and freedom, but it comes at the cost of stability, predictability, resources, and coherence.

Is it worth the trade? Well, I am here to offer a resounding maybe. That’s the bittersweet part. Independent creatives get to feel a unique kind of pride and flexibility, but we’re also acutely vulnerable because we are unprotected.

The only thing I wrote in my notebook during that first conference was from a talk by Christina Xu. Here it is—three little words:

“Independence is lonely.”

It still punches me in the gut years later. It is so obvious, right? Independence means you are on your own. You can do things your own way and claim all of the successes, but you must also define your path, endure all of the struggles alone, and own all of the failures. Independence is lonely. It feels true, but is it necessary?

The cartoonist Hugh MacLeod says the price of being a sheep is boredom and the price being a wolf is loneliness. My experience as a lone wolf says he’s right, but I also hope it doesn’t need to be that way. After all, wolves are pack animals and live together in caves. How can we be independent together?

A quick mental scan shows there are a lot of ways to work with other people. Here are three:

- Employment: Working for others

- Collaboration: Working with others

- Community: Working alongside others

Mix them up however works for you—each combination creates a different flavor of independence. I’m going to focus on community and employment, because they seem most appropriate for today.

Community

Community is critical for creative folks because creating the work is so inwardly focused. Each of us needs something to pull us out of ourselves, and we will invent batshit ways to do it if we don’t have community. I’ve worked in seclusion before, and after about two weeks, I’m talking to the house plants about my projects and imagining what internet strangers will think of my work instead of my friends and peers. Participating in a community becomes a way to let some sympathetic people into your process so you don’t go crazy, while still protecting the work in its unfinished and fragile state. I see community as people working parallel to one another, sharing information and resources freely with each other. This is how useful information spreads around and how creative people find new opportunities. Nobody knows how to make a community like creative people. We invented the scene.

Employment

Many people presume that employment is the opposite of independence, and that endlessly irritates me. It’s so short-sighted. History shows a long record of artists who did “normal” work to support their creative practice. If you work as a barista, graphic designer, or accountant to fund your writing or music: great! (You can swap out any of those job titles or passions with your own.) By keeping your day job, you’re in the fine company of T.S. Eliot, Herman Melville, Toni Morrison, and more.

There are a lot of good reasons to keep a job going while you make your work, especially if you have kids or you’re not fortunate enough to be young and healthy. But there’s one other important benefit to the unrelated day job: when it comes to your art, you don’t have to take any shit from anybody. You can honor any creative impulse because your paycheck is never on the line. Go nuts, make crazy shit. What’s more independent than that?

Not everyone needs a day job. I’m lucky enough to make a living doing the work I decided to pursue a long time ago. Some of you out there are the same. Still, there’s a lot to learn from the folks who are employed doing things that don’t fulfill their creative hunger. You can distance yourself from the work and properly prioritize it. Creative people have a tendency to identify too closely with their craft, so when work hits an unexpected snag, they suffer.

I want to share a quote from an interview with Krista Tippett. She hosts a great radio show and podcast called On Being. She says:

“I worry about our focus on meaningful work. I think that’s possible for some of us, but I don’t want us to locate the meaningfulness of our lives in our work. I think that was a 20th-Century trap. I’m very committed and fond of the language of vocation, which I think became narrowly tied to our job titles in the 20th Century. Our vocations or callings as human beings may be located in our job descriptions, but they may also be located in how we are present to whatever it is we do.”

You know that quote, “follow your bliss”? It was said by Joseph Campbell, a scholar who was interested, like Tippett, in our spiritual capacities and how they were expressed in the stories we tell. When Campbell told us to follow our bliss, he wasn’t telling everyone to chase their dreams until they became careers. He said it as a call for people to pursue a vocation as Krista Tippett has defined it. Vocation is as much about who you are and how you are as it is about what you do. Bliss is an attitude, a disposition, so meaning comes from a way of being and is not a consequence of producing work. You make the art, the art does not make you.

I’ll admit it: I identify too closely with my work. That leads to a lot of stress, depression, and doubt when things aren’t going well. I mistake the work’s flaws for my own. Perhaps that’s something many of us have in common. The way to approach this issue is clear: we must acknowledge we are involved in our unsteadiness, but believe we are only part of its reason. If we allow room in our work for serendipity to occur, that same space must also be reserved for misfortune. We are the cause of neither.

There are factors in our culture and creative environments that contribute to the turbulence of independence. I believe we have the power to change these things, so here are a few critical questions for us all to consider.

One

How do we create a cultural awareness that attention with art rarely leads to profit? It’s an old, pre-internet mindset that seems to persist. Likes and shares don’t buy groceries, so the mix up creates a lot of pain for those who have worked hard to get their work seen, yet are still unpaid or underpaid despite their popularity.

Two

How do we produce more equitable platforms where attention DOES equal proportionate money? The core of this problem is that discovery is easier for audiences if they have fewer destinations (for example, find it on Youtube). But this situation also consolidates power and invariably leads to exploitation. What makes things easier for the audience eventually makes things unsustainable for the creatives. How do you break that cycle so we don’t rely on the perceived benevolence of those platforms?

Three

How do we build up services for independent artists that act as a sidekick rather than a toll booth? This provides access to resources and expertise for everyone, and opens up independent practice to the people who are wise enough to see the difference between Do-It-Yourself and Do-It-All-Yourself-And-Probably-A-Bunch-of-It-Pretty-Poorly.

Four

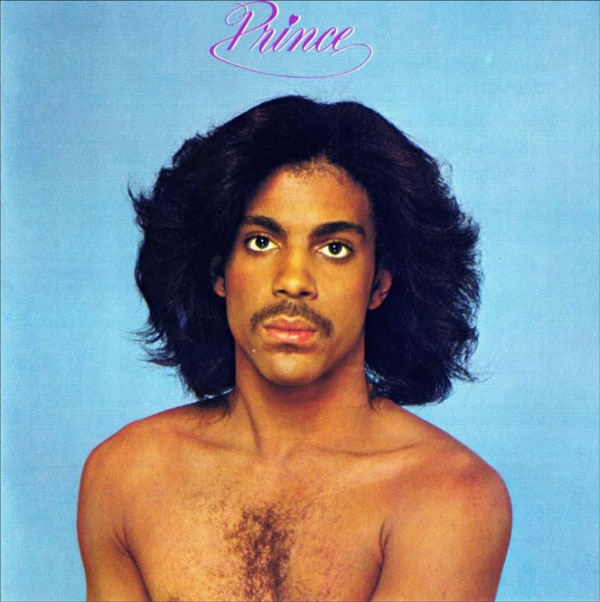

If you’re fortunate enough to have an audience, how do you honor them without giving them too much power over you? And, as a fan and someone who supports independent creative people, how can I be more constructively supportive? The last few weeks I’ve been thinking a lot about Frank Ocean and all the pressure placed on him before he released Blonde. Enthusiasm is gold, but hype only hurts everyone. I know this is a problem of success, but if we want success for ourselves and our peers, we must also contend with the problems that come along with it. Otherwise, a creative career turns into a long climb up only to fall off a sheer cliff.

All of this is important work that seeks to change our individual situations and the culture that surrounds us. It will take a community effort to address and improve. The key will be producing terms that are beneficial for everyone. In a way, this effort is an attempt to de-commodify creative work, reject the perceived replaceability of individuals as “talent” and art as “content”. If we truly believe creativity is a life-long pursuit, we need to develop sustainable ways of engaging with each other that value the longevity of the work and the people creating it. It’s a fair trade: to get the fruits of each other, we must take care of each other. Independence is always supported by interdependence.

Let’s go back to the cave. While I was researching El Castillo, I found that there were several other caves sprinkled around Spain and France with art from the same period. My favorite, though, was in Argentina at a place called Cueva de las Manos—cave of the hands.

Not one hand, but several. Not one person, but many. Not one time, but years and centuries, going from the Paleolithic to the Bronze Age and even just a few hundred years ago. We have been returning to the cave for a long time to leave our mark. We are walking that dark path together.

People’s hunger to make things is inevitable, but it is also malleable. Will we choose to go alone or shall we go together?