Making the Bed You Sleep In

If I had to describe my philosophy toward technology, I’d say I aim for the crux of whatever works the best with the least amount. You add things until it starts sucking, take things away until it stops getting better.

We’re looking for that sweet spot, the thing that fits just right, plus or minus zero. With that said, this isn’t a zen, simple living blog post. By being an apostle for nothingness, we lose touch with reality. Philosophy is worthless if it is not practical. My intent is to be helpful and useful, not dogmatic. Your mileage may vary, if only because of differing needs.

- Fit is paramount

- Access trumps ownership.

- Matter matters. Atoms must fill a need.

- Tend toward beauty in looks and elegance in use.

- Optimize for steadfastness.

I think the satisfactory outcome is freedom and autonomy: the ability to say both yes and no. I think often times we cast freedom as merely the ability to say yes to the things we want, but let’s face it: it’s usually easy to exercise that freedom if you’re a lucky citizen of a modernized country. We’re a culture prone to indulgence, and usually the times we deny ourselves the freedom of doing or having the things or experiences we want are the instances that courage is required to commit. These would be things like quitting your job and starting your own business, or booking a 3 week romp in southeast Asia. That courage is something that Appropriatism, or any other mode of thinking, can’t give you. One just needs to summon it in themselves.

What I mean by freedom is the ability to say no. I don’t consider this a negative way of thinking, but rather a very positive way to have permission to opt out of the things we don’t want to do. I feel we need to acknowledge the value of the freedom derived from simplifying and eliminating the useless things in our life. This means having an understanding of what’s important.

Not to get zen master on everyone, but there’s a natural dissonance that occurs when the things that matter more are at the mercy of things that matter less. On a large scale, this is what creates the drama for a show like Hoarders. On a smaller, more realistic scale, it’s losing a bit of our attention because it’s devoted to that nagging feeling that we’re not where we should be, not doing what we should be doing.

Let’s dive into a few of these core ideas in more depth.

Fit

Fit is the most important part of Appropriatism. This means clothes, technology, work relationships, projects, and anything else you can jam through this way of reasoning. Why is fit so important? Because a good fit means that there’s an understanding of what’s suitable.

Bad fits make us curmudgeonly. We loathe what we have because it’s not quite right. It injects friction needlessly into processes we wish were fluid. A bad fit restricts movement, and life is about movement.

Have you seen a man in a perfectly tailored suit? It’s made for them, and no one can wear it quite like they do. It’s full mastery of a piece of clothing through customization. This is what we want from everything we let into our lives: a good fit, so we can achieve full mastery of our tools, so we can milk all the potential out of everything that we have. If we can do that, we can truly appreciate our things.

Access

Access trumps ownership, because access denotes utility and ownership means maintenance. If you’re not sure what that means, compare the experience of joining a gym and having access to a treadmill versus buying one of your own. Often times I think we celebrate the convenience of ownership (“I can run anytime I want without leaving my house!”) and forget the demands of maintenance (You need to have space to store this contraption, and when it dies, you have to fix it yourself.)

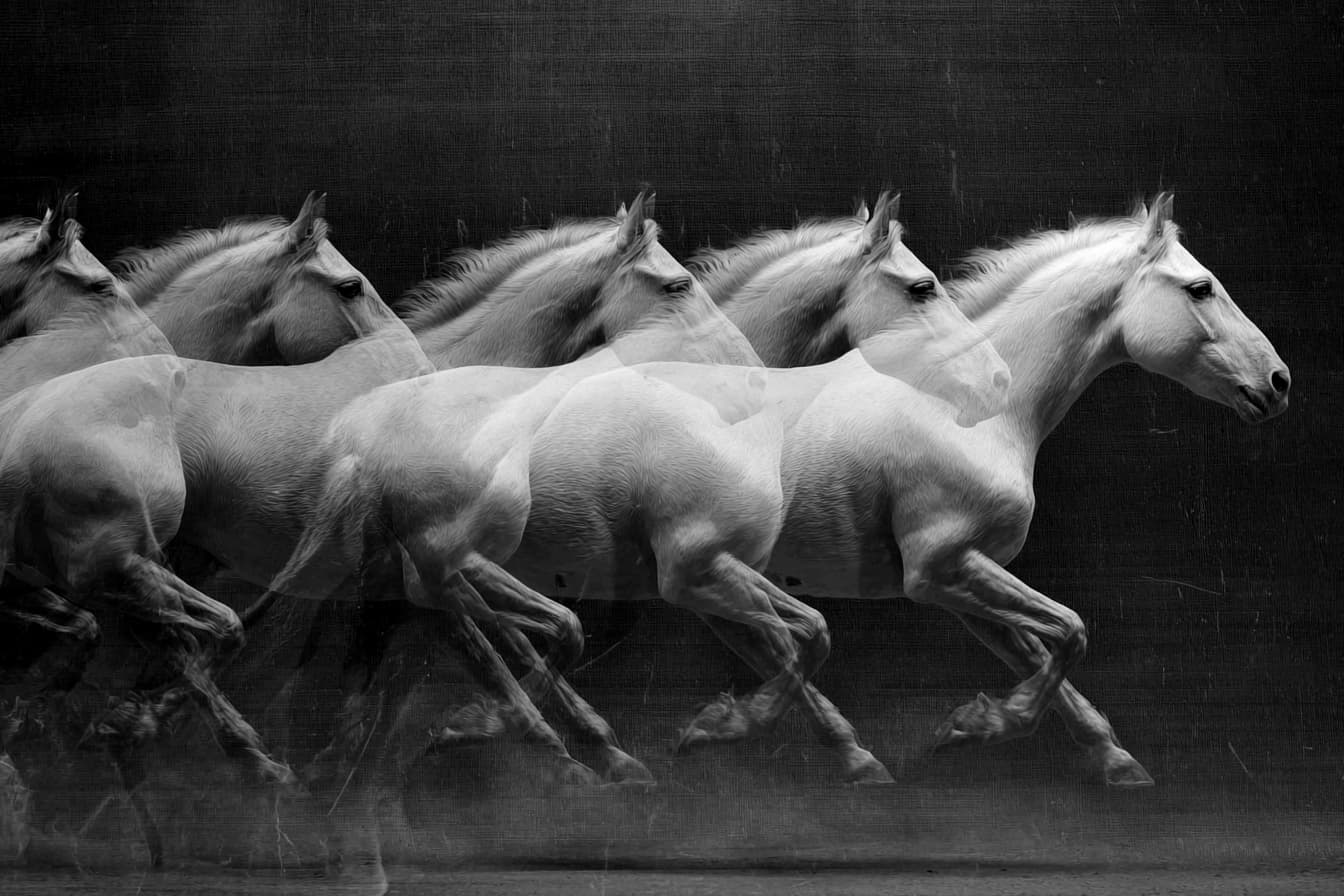

There’s no place where this stampede from ownership to access is more evident than with media. Netflix’s Watch Instantly is the harbinger of the death of media ownership. When access is seamless, the experience of enjoying that media is just as convenient as ownership (actually, I’d say it is frequently better.) If you’re not sure whether or not you value access over ownership, consider the fact that last night you probably chose what movie to watch based not strictly on what you wanted to watch, but rather what you wanted to watch and what Netflix had available to stream.

Of course, access over ownership with media is no new thing. Libraries have had this concept pegged since the Ptolemaic dynasty built that big one in Alexandria in the 3rd century BC. With the magic of digital distribution, however, we’re no longer restricted by the number of copies on the shelf: we can produce infinite copies without leaving our homes. No reason not to take advantage of that, right?

So, can you make do with a ZipCar instead of owning a car? A gym membership instead of buying that treadmill? What about just borrowing stuff from friends? The less frequently we use something, the stronger the argument for valuing access over ownership. Sure, valuing access over ownership usually requires a bit of forethought, but you’re trading that effort for flexibility and lightness.

Beauty & Utility

If access trumps ownership, when should we own things? I’d say when they’re manifestly important, and only in the best format we can afford. Truth is, it’d be a total shame not to own a single book, because there’s something about the things that’s valuable in constructing an identity. Scanning someone’s bookshelf is like peeking into their cognitive medicine cabinet, so go buy those books that made you who you are, but buy them in hardback and the best copy you can find. The important books, albums, and movies are a little piece of you, and they deserve to be treated as such.

If something takes a physical form, it must fill a need. These needs can be emotional needs or the needs of day-to-day life. I need a broom to sweep my apartment, but I also need that painting by my friend Pete on my wall because it reminds me of my friends in Chicago and also what it was like when I was first setting up my design practice.

When we choose to have physical objects in our life, we need to make sure the need is real. Is that art really filling an emotional need if it’s in a drawer and not on display? When’s the last time I used that coffee pot as opposed to the french press? (Cited from personal experience.) And what of redundancy? Do I really need a broom and a Swiffer sweeper? Why do I have 3 different kinds of tongs? Jesus, what am I doing with my life?

If the need is real, we should always tend towards beauty in utility, and when possible, beauty in form. Be wary of objects that are beautiful in form, but less than satisfactory in utility. Any one can tell you that an iron that looks like a plastic rocketship isn’t going to do the job very well. However, sometimes, we get objects that are both beautiful in their form and graceful in utility, like a Shaker broom. When both occur, we’ve achieved something that has steadfastness.

Steadfastness

Steadfastness refers to the longevity of utility. Obviously, a well constructed pair of shoes can last a long time, and can last even longer through resoling. Common convention says that it’s good practice to invest in things that will last.

We can also achieve a certain steadfastness in unpredictable or quick to change areas, such as technology. We do this by identifying the needs that are steadfast and the devices that fill those needs, and labeling the parts of the system that are “hot-swappable,” meaning that they can be replaced quickly and easily without bringing the whole system down. (Also see this great blog post on steadfast components by Robin Sloan.)

For instance, if you’re a film buff, owning a nice television or projector would be a steadfast purchase. The utility of a nice picture will never change. What will change, however, is the technology that feeds that picture to the screen, whether it be an AppleTV, a DVD player, or a BluRay player. So, investing in a nice screen is manifestly more important than investing in a top of the line BluRay player. The devices that hook into the television are hot-swappable.

How about computing? Things are a bit different here, where the steadfast component is your data. So long as the speed of a computer is sufficient, the most important aspect of your computer usage is mastery of your tools (software) and access to your data. So, one should invest time into choosing the appropriate tools and learning them well, and money in spacious, stable storage. Storage takes the form of external hard drives, an automated backup system, and solutions that sync data to make it easier to hot-swap your computer as your needs change or as innovation ceaselessly marches ahead.

Need more examples? Men’s style doesn’t change very much from year to year, so a wise guy would invest in a steadfast watch, shoes, jeans, pants, and coats. (The more steadfast the item, the greater incentive there is to buying it used.) The hot-swappable item that changes with fashion from year-to-year is the style of shirt. There’s no harm in embracing that.

Ultimately, all of this involves thinking hard about the requirements of the situation and assessing what needs are likely to change and which are not. Optimize for steadfastness, embrace the ephemeral quality of hot-swappable items when it makes sense, and think about how it all connects.

In the end, I think the most important thing to recognize is that we’re now living in a world of excess. Excess data, excess access, excess “stuff.” Our behavior and mindset should change accordingly. The discussions we have should not be about consuming less or having more, but rather “What is better?” and “What is appropriate?”