Tarkovsky’s Flame

When the world is brash, fast, and stupid, we must seek out what is quiet, slow, and intelligent to brace ourselves against the world’s madness. I have been under the influence of Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky’s movies for the last few weeks, finding them to be a source of the comfort and beauty which the world seems not equipped to provide right now. Tarkovsky’s movies could be interpreted as sad, but it is a typical American trait to mistake slowness for sadness.

America’s dysfunction is now wed to its antagonistic relationship with Russia, and I take comfort that the Russian powers that be did not care much for Tarkovsky either. They found his spirituality, ambiguity, and grandiosity dangerous, so they embargoed and delayed all of his films. But I adore well-earned spirituality, ambiguity, and grandiosity, so of course I like Tarkovsky too. Everything his countrymen found dangerous about his work I find essential.

I’m not alone in thinking this: throw a Criterion Blu-ray far enough and you’ll hit a group of cinephiles fawning over his seven movies. Some even say they are the best films ever made, and I agree on many days, simply because Tarkovsky’s films speak to the patient and deep parts of me I want to nurture, without being naive about the difficulty of doing this work.

The quality of what we receive from art is limited by our ability to pay attention to it. Tarkovsky’s films take attention and patience: they are slow and ponderous environments to experience. Usually there is no clear story. This will be frustrating to many people, which is no fault of theirs (everyone comes to a movie with different expectations), but it is important to point out that so many crowd pleasers were born from his films. Movies like The Revenant and Inception play checkers with Tarkovsky’s chess set. What these films lack is also what the world needs, and what I find myself hungering for in every aspect of the made world—whether it is film, internet culture, or politics. I have heard others long for it in many different ways as well, so I will risk triteness and say it direct: we need grace; we need tenderness; we need depth; we need soul.

These things, of course, must be applied to everything we do, but what we give our attention to is a good place to start. So why not give a Tarkovsky film a spin and see if you like it? Mosfilm, the major Soviet-era Russian film studio, has uploaded most of the Tarkovsky filmography to YouTube in high-definition, for free with English subtitles.

My favorite film is Mirror and its dream logic, but the anti-war Ivan’s Childhood is probably a more accessible starting place (it’s where I started, too). You can also go watch the two-part Andrei Rublev, a story of a 14th century Russian icon painter focused on the mystery and travesty at the heart of creation (it’s considered by many to be the most beautiful film ever made). Another favorite is Stalker, which is difficult to describe in the same way as Waiting for Godot. Stalker, like each of Tarkovsky’s films, is its own thing.

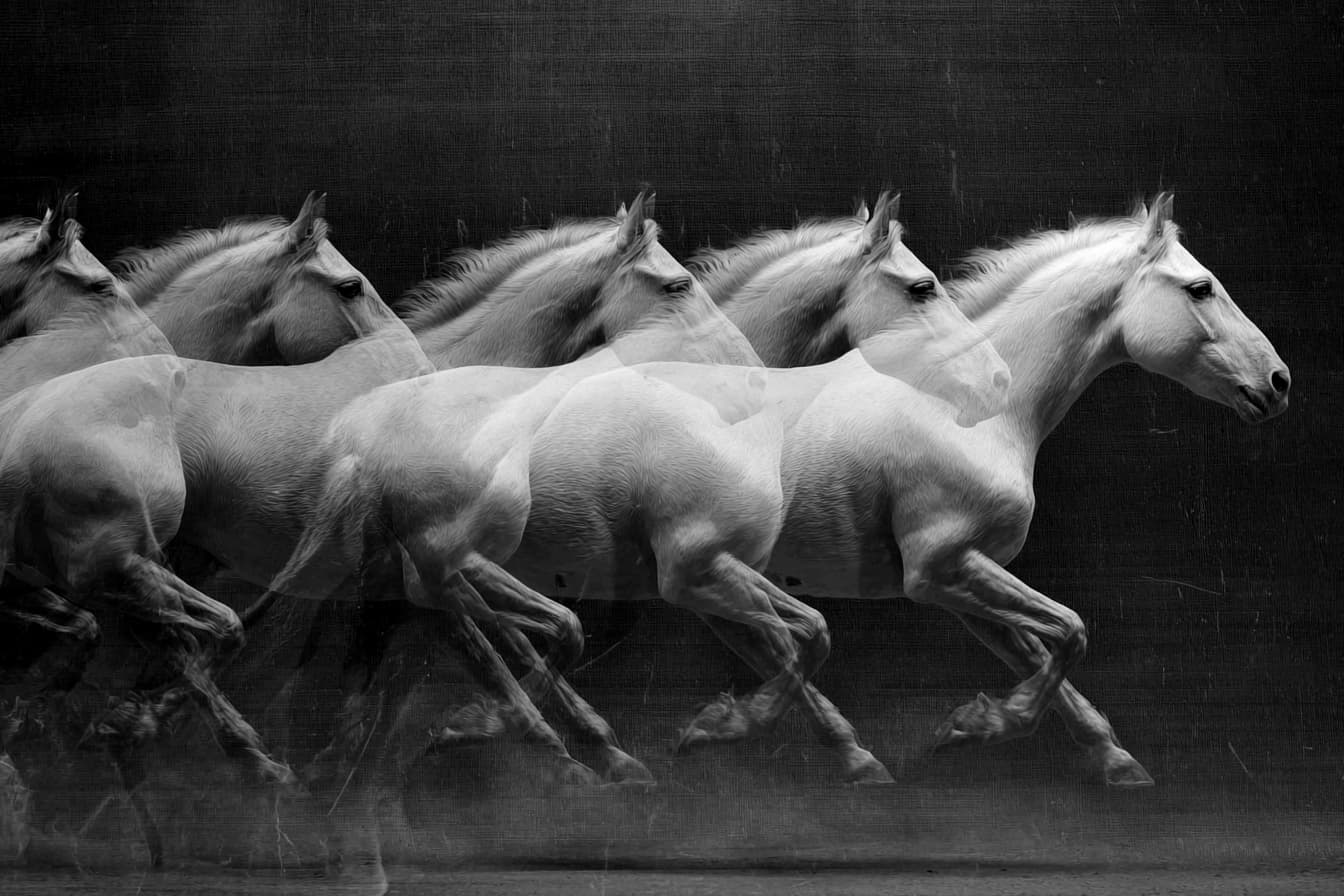

Tarkovsky combined poetry, painting, and philosophy to form his own unique language for cinema, and in the process made some of the most beautiful and deeply moving images ever put to film. The language barrier and cultural divide does not matter: these images are potent and primal. There are two or three shots from each of his films which will linger with me for the rest of my life, and I can’t say that about any other director.

Here is small inventory of these living images, which should be immediately recognizable to other fans:

- the well

- the chase through the aspens

- the kiss over the trench

- the boy running on the beach

- the balloon drifting away

- the bell forging

- the family huddled together in bed

- the writer wearing his crown of thorns

- the glass shifting on the table

- the grass in the water

- the thirty seconds of weightlessness

- the finch on the fingertip

- the red pants in the snow

- the house on fire

- the other house fire

- the man on fire

- the rain, even indoors, every where: rain

There is one important image from Tarkovsky not in this list, because of its special status. A poet carries a candle across an abandoned pool, meant as a tribute to his passed friend. His progress is excruciating—a 9-minute, continuous shot of him protecting the weak flame against wind and water.

Everything flickers, even the spirit. There are times with more light and times with less. And what are moments of illumination but briefly felt truth?