The Humble Pencil, The Mighty Computer

Creative people tend to romanticize their tools. We place them on pedestals as the conduits for our ideas and the enablers of our craft. Contrastingly, though, I think all creatives believe that a good tool does not make a good designer, and a good designer does not need top-of-the-line special tools. In fact, I’d say all one usually needs is a pencil and a sheet of paper. With that, one can wield the power of visual communication like a sword, a lullaby, or maybe even a stick of dynamite.

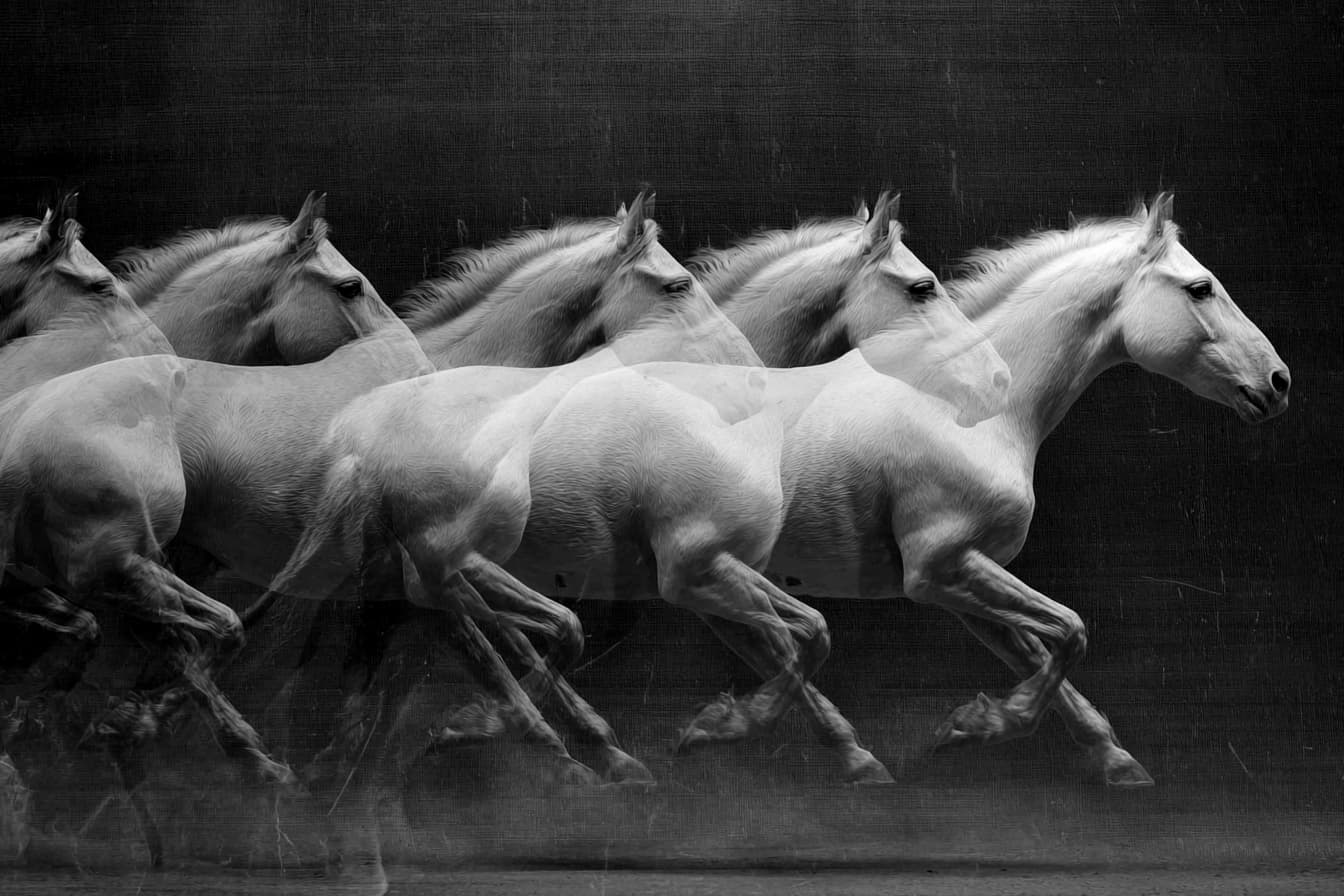

Pencils are special things to me. They are humble in materials: just a bit of wood and graphite, but when together, they represent the potential of a productive process. If you were to ask a friend to imagine a scene where someone is coming up with ideas, they would probably see a person at a desk with a waste basket beside it filled with a pile of crumpled paper. It is curious that waste is the main denotation of productivity. The bin would overflow with the ideas that weren’t good enough. Somewhere in that scene, maybe just a bit out of frame, there is a pencil scribbling wildly on paper. The more inspired one is, the faster that pencil moves. The harder one works, the shorter that pencil becomes. There are metrics in a pencil.

The pencil is general, yet specific. Ideas can be hashed out with ease to gauge their potential. The marks can be vague enough so one doesn’t judge the execution, but instead judges the potential of the idea. This is why I can’t come up with ideas on computers. Computers are too specific; they have too many degrees of separation between my mind and the canvas. With a pencil, it starts from my brain, moves down my arm, straight out my hand to the paper. Atoms transfer from the tip of the pencil to the surface of the paper. I can see the sheet fill up. With the computer, I have to turn on the computer, grab the mouse, launch the software, select the tool I wish to use, think about how to use that tool, and then worry about the mark that it makes. The beauty of a pencil is you don’t need to think about how to use it. It’s instinctive. A five-year-old knows how to use a pencil just as well as a sixty-year-old. The pencil is the great equalizer.

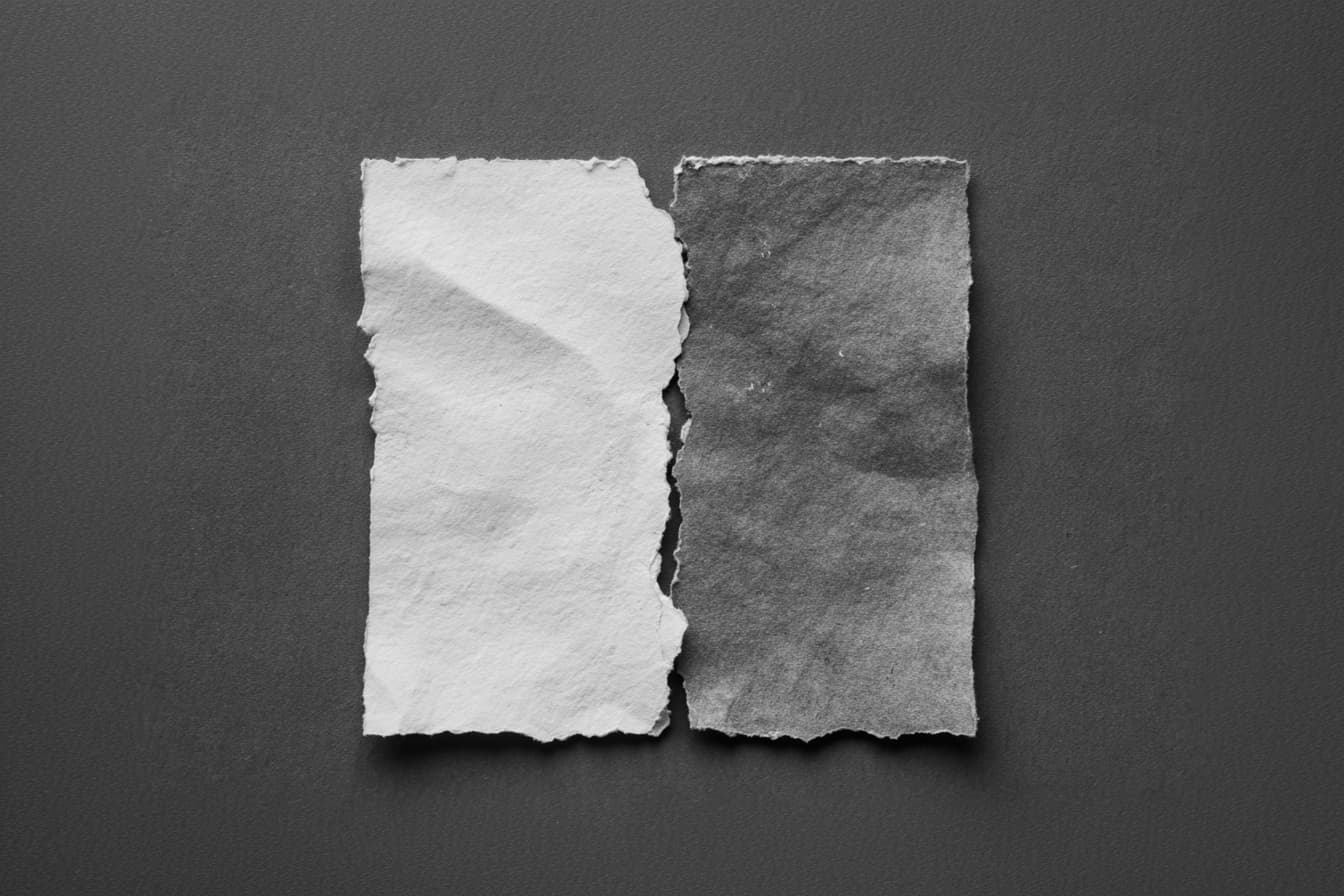

Computers have an infinite canvas, so I can’t feel like I’ve filled one sheet to start on another. Imagine reading a book with no chapters: every word just runs into the next without a rest. That’s how it sometimes feels to be working creatively on a computer: an endless journey with no edges, no sunsets, nothing to denote the end of one thing and the beginning of another. There’s no pile of paper to look at and to say “Look at all this ground we’ve covered.” Every mark has the finish of a final mark on the screen, and ideas in progress do not look how they should.

Process work on the computer looks like a messy version of something late in the process. With a pencil, process work, if drawn right, looks like a tight version of something early in the process. There needs to be vagueness in execution and clarity in concept and strategy at the beginning of a job, and I find that when I start on the computer, the opposite usually occurs. I have a tightness to the execution, and a vagueness in my concept, and that is a truly undesirable, frustrating place to be. It means one might be giving form and structure to something that might not be worth it. They are laboring on making something beautiful, when they’re not even sure if it’s the right thing to be doing.

When I start a new project, I think my initial tries at the idea should look like the final result through squinted eyes. I can do this with relative ease with a pencil and paper. On a computer, it’s a bad facsimile of what I want. It’s my idea reflected through a funhouse mirror. What I want gets distorted because the computer gets too specific too quick: I start focusing on if things line up instead of if I’m even saying the right things.

That’s not to say that there are no benefits to using the computer. Computers are wonderful for automating difficult or complex tasks. They do a great job of removing human error, cleaning up execution, and providing a tightness to the final product. But, they don’t help in the beginning when a designer is flailing around, searching for an idea they can be confident about. In the beginning, quantity matters, because quantity usually edits down to quality. Quick execution and cheapness matters: I find myself censoring myself less with a pencil and paper than on a computer, because I can do a drawing quickly. Mistakes are cheap with a pencil and cost a lot of time on the computer.

There are real benefits to working in physical space. We can approach our work in new contexts. We can draw something, then cut it out, and move it around. We can touch what we produce, and we can judge our progress on a project by the height of our pile of drawings. I think an important part of the creative process is play, and for me, it is easier to play in physical space than digital space. I think tactility is an important part of playing and planning. It’s why we love Post-It Notes. Getting things down on paper opens innumerable options: cutting, tearing, folding, gluing, collaging, drawing on top of what you’ve already drawn, and, at worst, just crumpling up the paper and starting again.

And maybe that’s why I prefer the pencil. It forgives me for my mistakes: there’s an eraser there, after all. It accepts me for who I am: I can use it however I wish, and I don’t have to learn any special means to operate it like you might on a computer. There are no “rules.” And the pencil will always be cheap and available to anyone. I like what that represents: everyone has what they need to make something incredible.

This was written for Hand of the Graphic Designer, an exhibition sponsored by the Fondo Ambiente Italiano in Milan, Italy