Portraits

Good art is pointable. Something complex occurs, and you can’t quite explain how you feel about it. Instead, you find the appropriate book, song, poem, whatever, then point to it, and say “That. That is how I feel.” It’s a shorthand that stands in place of your own words. It speaks for you.

That’s what led me back to Velazquez’s Las Meninas.

The simplest way to think about Las Meninas is as a painting about being painted. Western art has its fair share of notable portraits—DaVinci’s Mona Lisa, Vermeer’s Girl with the Pearl Earring, Warhol’s Marilyns and Elvises—but of art’s grand works, Meninas is the only portrait of its viewer, depicting the process of being observed and rendered. The painting is deeply unsettling, because Velazquez himself is creeping behind the canvas—staring, measuring, judging, while his brush hovers above the palette. He is remaking you to an audience, but that canvas stands stubbornly away from your view. You are being reproduced, but that reproduction is inaccessible. Increasingly, this is how I feel about technology.

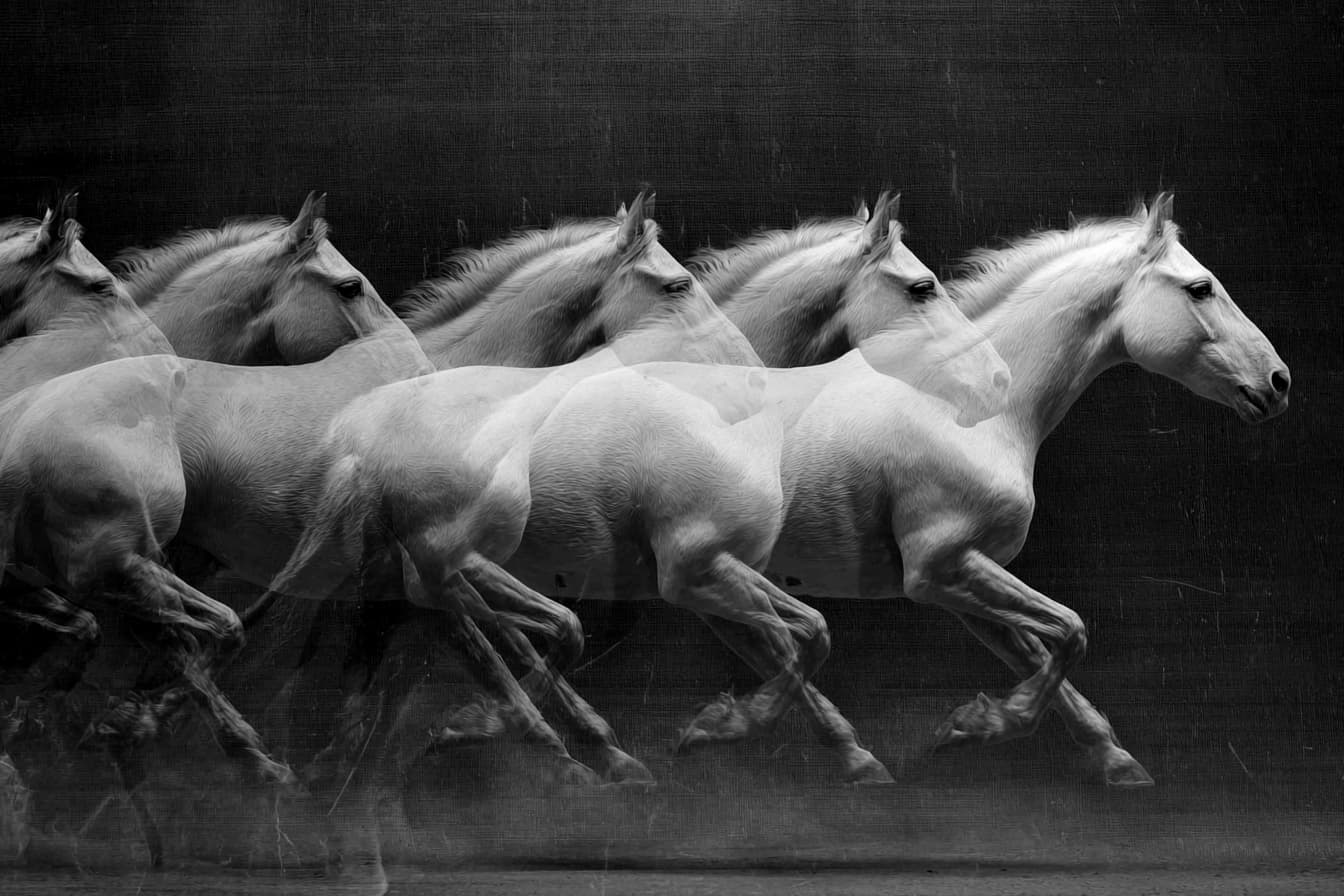

One of the more bizarre things about modern life is that everything you do produces data, and these by-products can, in theory, be reconstituted into some sort of likeness. This belief forms the foundation for everything from Facebook’s advertising platform to the NSA’s PRISM program. All one needs is an insatiable appetite for data, the bottomless belly to store it, and the brain to make sense of it. Enough email forms a persona; enough likes produces a disposition; enough GPS coordinates suggests predictable behavior. From there, one can paint a picture, and that picture can be sold to advertisers or used as evidence or leverage.

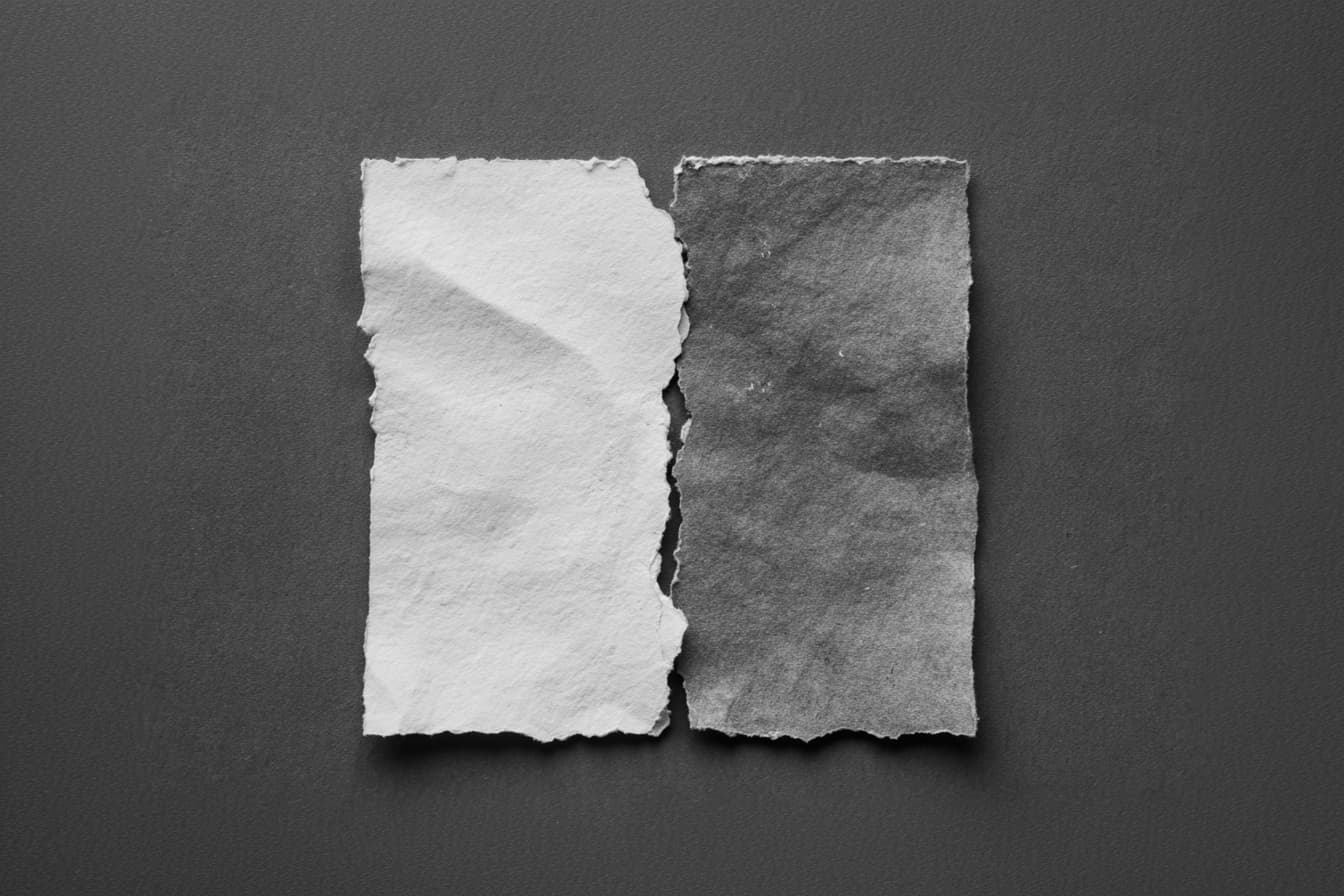

I am unwittingly having portraits painted of me, and you are, too. Perhaps this is the cost of modern technology: by being connected, you grant one of these tubes—be it Verizon, Twitter, Facebook, PRISM, or anything that contains data in aggregate—an attempt at your likeness. At this point, the value of a portrait is unknown, so both painter and subject are willing to go along with the tenuous arrangement. The painter thinks they can capture a valuable and useful likeness; the subject either believes the portrait will be distorted, or is unaware they are being painted at all.

The institutions that call for radical transparency very rarely exhibit it. Facebook will always know more about you than you will know about it. Google will be the only one to know how all your emails coalesce into a more meaningful picture. No one knew PRISM existed until a few weeks ago. We might know that we’re having portraits painted of us, but we will never have the canvas turned in our direction. And, if these painters did turn their easels around, I’m not sure which would be more terrifying to see: a distorted, monstrous version of myself, and say “that’s not me,” or myself mirrored back, reconstituted—the exhaust fumes of my day-to-day life somehow made solid.