The Cloud Is Heavy and Design Isn’t Invisible

Timo Arnall’s dismantling of the “invisible design” ethos is a rousing read. There’s too much I want to talk about in the essay, so I’ll settle and highlight one choice bit that runs parallel to something I’ve been considering myself.

We already have plenty of thinking that celebrates the invisibility and seamlessness of technology. We are overloaded with childish mythologies like ‘the cloud’; a soft, fuzzy metaphor for enormous infrastructural projects of undersea cables and power-hungry data farms. This mythology can be harmful and is often just plain wrong.

A metaphor can clarify or obscure. The most dangerous ones do both. They illuminate one characteristic of a concept, but also throw another (usually less favorable) aspect into shadow. “The Cloud” is one of these complicated metaphors, because it’s a clear description of the user’s experience, but overlooks its costs by misrepresenting the situation. Storing data on servers is light, accessible, and omnipresent for the user. But The Cloud is not a dissolution of data’s “weight”; it simply outsources its handling, in much the same way your garbage doesn’t disappear when it’s picked up from the curb. It’s a complicated transaction, because the true implications are hidden. Still, I wouldn’t want to get rid of the Cloud or my garbage pick-up. All this stuff has to go somewhere, and generally it’s better if I’m not the one toting it around. So, my garbage goes somewhere in New Jersey, and my data goes to Douglas County, Georgia.

It’s worrisome that The Cloud as a metaphor clarifies the benefits of its user’s experience, yet hides the repercussions of that convenience. (Of course, it’s old hat in capitalism to conceal the unsavory bits of production behind a curtain.) What kind of energy does that data factory use? Where does it come from? And how does it compare to the energy used if we kept all this data locally? How does that building affect the community where it is built? And what are the repercussions of having all that data in one place?

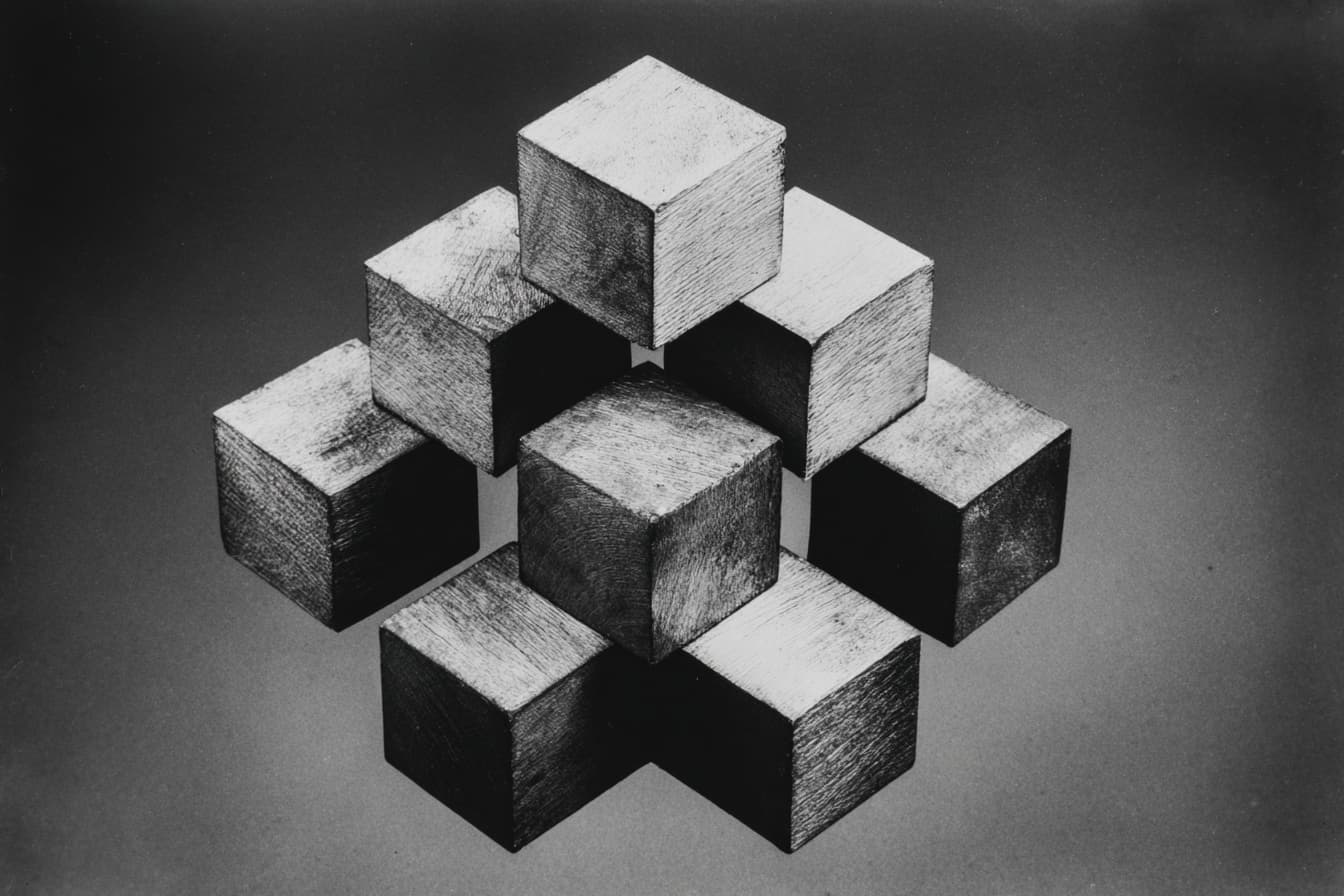

The answers to these questions don’t need to be awful. For instance, many of these data centers are blanketed with solar panels to collect energy and offset or eliminate its dependence on the grid. Google’s not trying to hide anything. In fact, the image above comes straight from them. Yet, I believe it’s important for users to ask these questions, if only to understand their dependencies. Still, it is hard to know what to ask if the topic’s complexity and requirements (infrastructure) are concealed by the metaphor that names it.

All of this is well-trodden territory, so I’ll sheepishly confess that I’ve backed into the real reason I wanted to write a bit. There’s another loss from this kind of obfuscation, one more miraculous in nature, which also undermines the “invisible design” ethos.

Look back up. Isn’t the picture of Google’s data center marvelous, in a complicated Dr. Seuss machine kind of way? It is like a Pipe Dream level come to life. The ethos of invisible design suggests you shouldn’t see this design. I think you should look again.

Sometimes I wonder if the desire to obfuscate production and make the resulting design invisible or seamless to users diminishes their appreciation for the craft of building systems. I think there’s a strong likelihood that metaphors like “The Cloud” and sayings like “It Just Works” reduce a user’s appreciation of the software/hardware they are using. “Magic” is a great word for selling product, but it also can cheapen all the sweat it takes to get there. If the seams have been covered, you can’t admire how things connect.

Design doesn’t need to be showy to prove its value, but it shouldn’t be invisible, either. Designers mistake invisibility for elegance and simplicity for clarity at their peril. The best design speaks not only so it can be understood, but also in a way it can be admired by those that use it. What if you were inspired by the things that you used, simply because they were impressive in a way that was evident to you? And why is it bad to try to build things like that?