Hi, I’d Like to Add Myself to the New Yorker

A few months ago, I stumbled into the little cottage industry of media manipulation. I weaseled my way into international publication, collected accolades left and right, then moonwalked out. I wish I could credit all of it to cunning, but this is just another story of an idiot hero. It’s a convoluted story, so best to start at the very beginning.

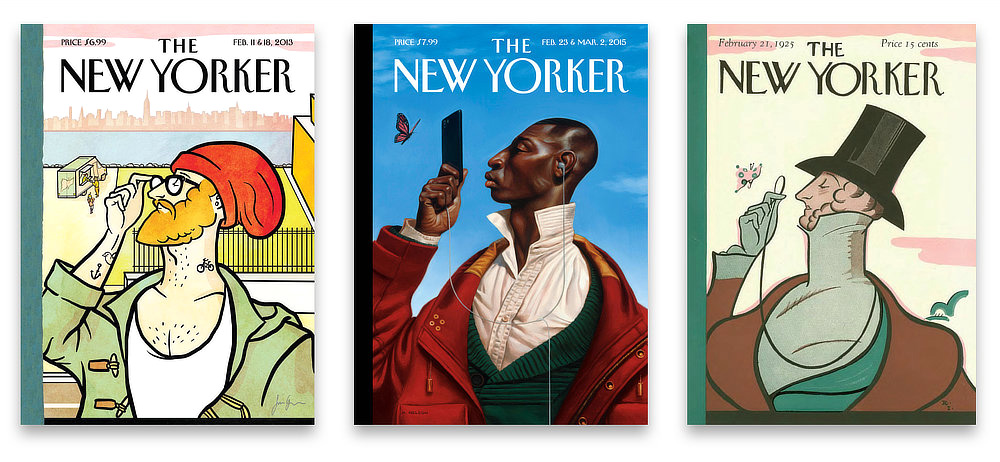

The New Yorker is a literary lifestyle magazine founded in 1925. It focuses on a kind of snooty cosmopolitan sophistication that I, as an overly self-aware and anxious Brooklynite, eat up like candy. The magazine publishes a fine mix of short fiction and longform journalism, and stays loyal to its namesake by covering the goings-on in New York. Yet out of everything they publish, most are familiar with the cartoons. The irony is deep. Renowned for its prim words, we flip through The New Yorker to look at its screwball pictures.

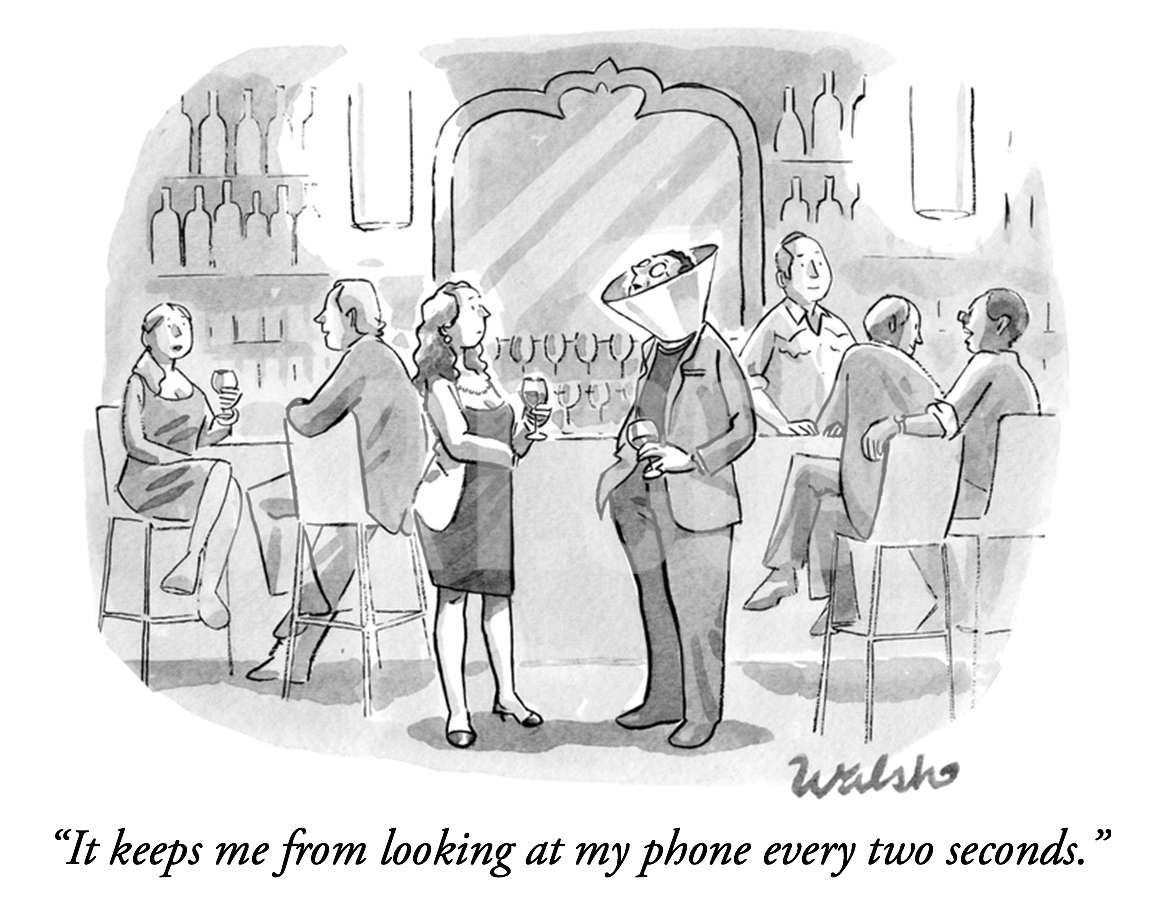

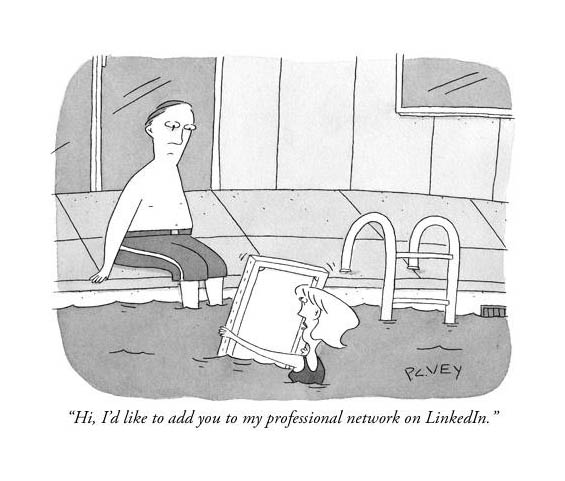

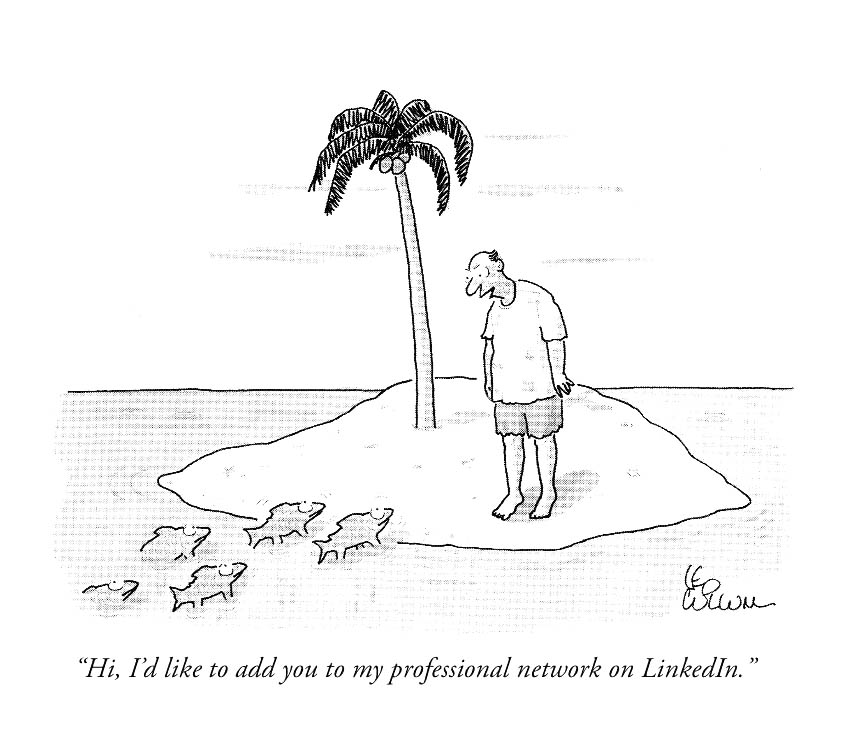

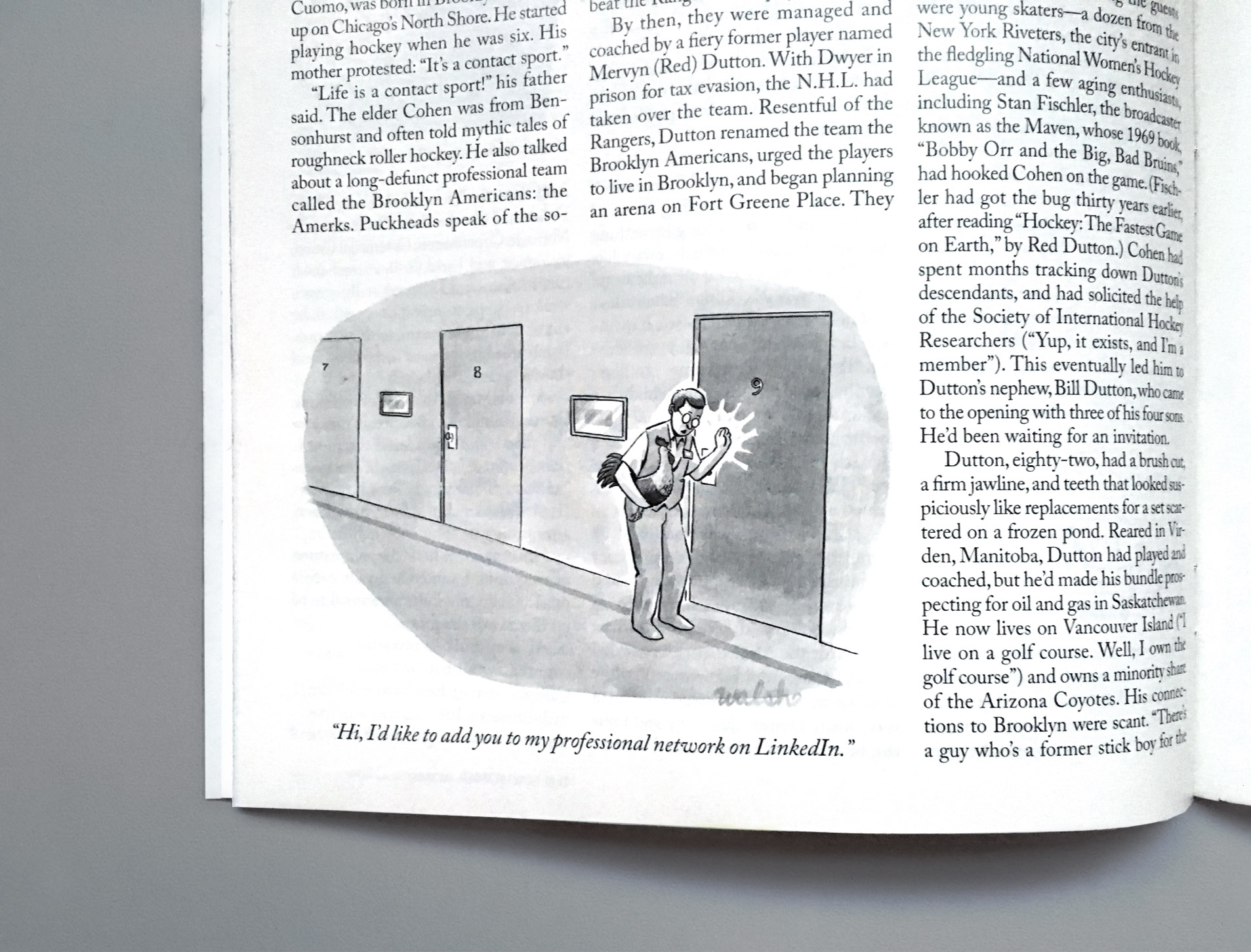

Just in case you’re unfamiliar: the cartoons are typically a black-and-white illustration of two people in a bizarre situation speaking to each other.

Typeset underneath the drawing is a wry caption that undercuts the wackiness of the picture. Like so:

While the illustrations are great, the captions are the hook. There’s an overwhelming urge to rewrite the text, kind of like how advertising in public spaces inspires graffiti. It begs to be defiled, especially since it seems like it would really piss off the magazine.

But that simply isn’t the case: the staff encourages this kind of behavior. Each issue has a caption contest to find the best match for a lonely illustration. This invitation, of course, becomes an opportunity for impishness. There is a seedy underbelly of prospective New Yorker caption writers, and they have been working for years to define the ultimate caption, one that works for all New Yorker cartoons, ever.

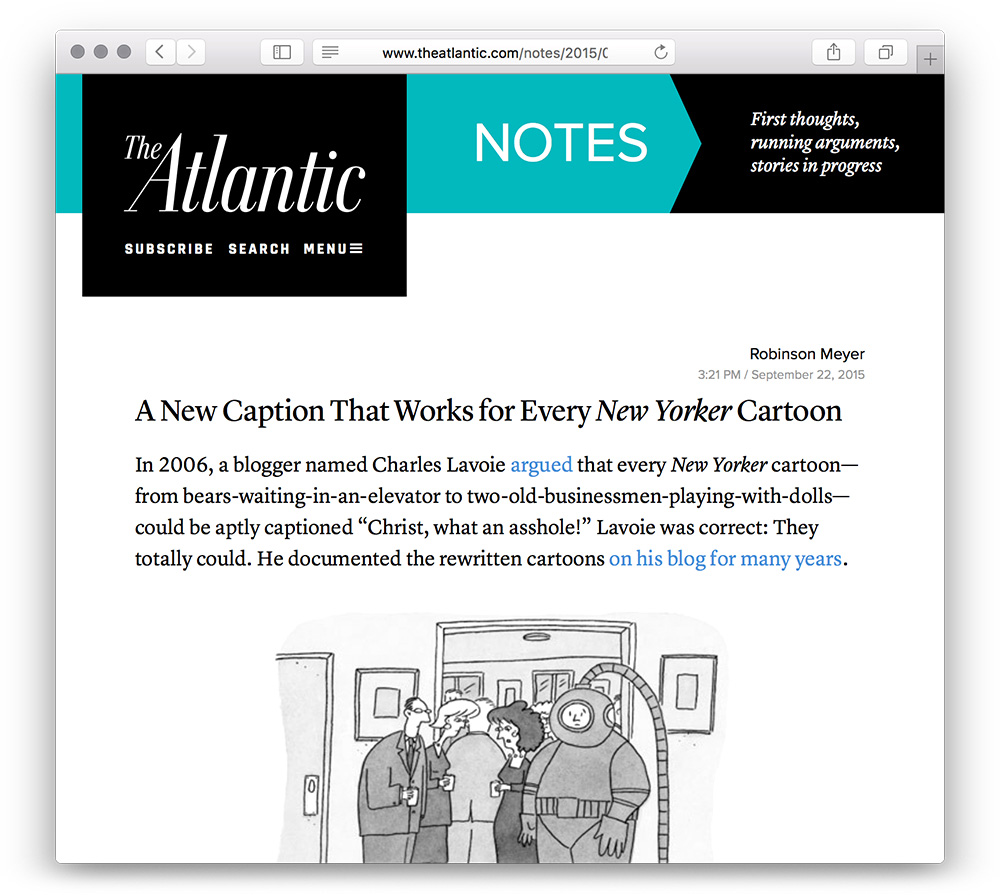

Their efforts have delivered two famous über-captions. First, there is the descriptive, “What a misunderstanding!” by artist Cory Arcangel. Next, the suitably dry, “Christ, what an asshole!” by Charles Lavoie. Some other wooden options linger around the internet, but they lack the humor and timeliness of a great New Yorker caption. The über-captions on record are blissfully unaware of selfie sticks. They have no ennui about our hyper-connected society, no opinion of Drake. Clearly, we can do better.

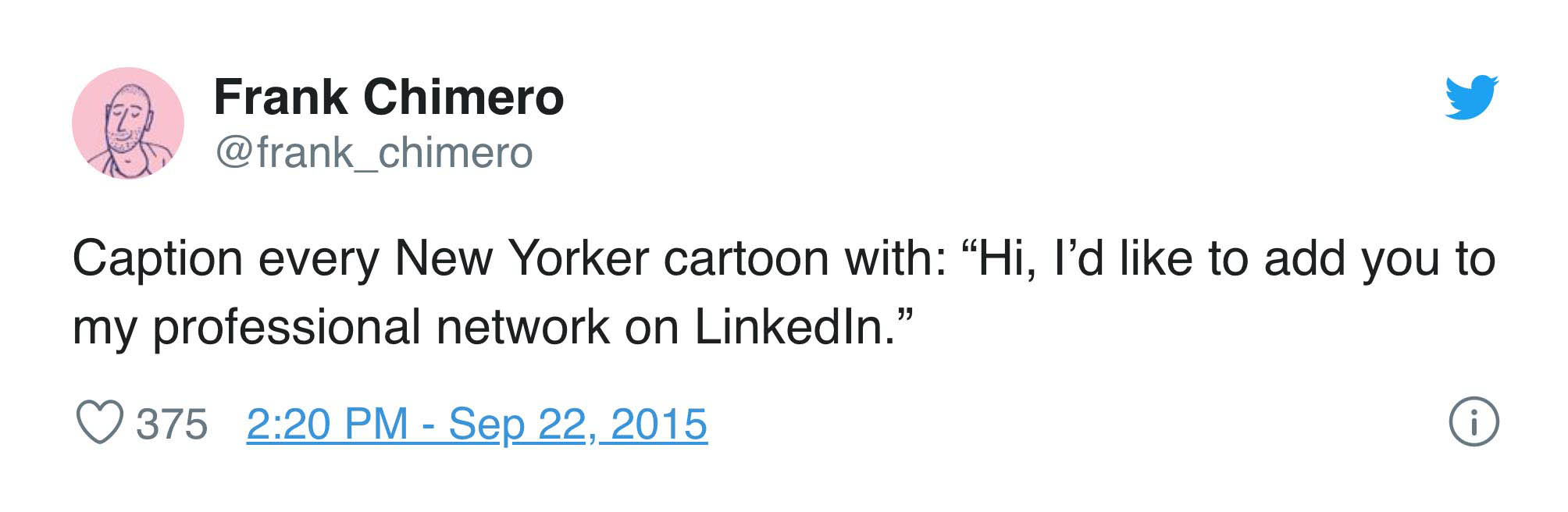

I gave this situation about twelve seconds of thought, and stumbled upon a universal caption of my own. And, like any thought that takes twelve seconds to think, I put it on Twitter:

If you’re laughing, you know of LinkedIn and its emails. If you haven’t heard of LinkedIn, you’re lucky. Just know this is the subject of an email many people get daily. It’s dubious in value, allowing the lazy, exploitative people you want to speak to the least to take up the most amount of space in your inbox. It is brazen idiocy that won’t quit.

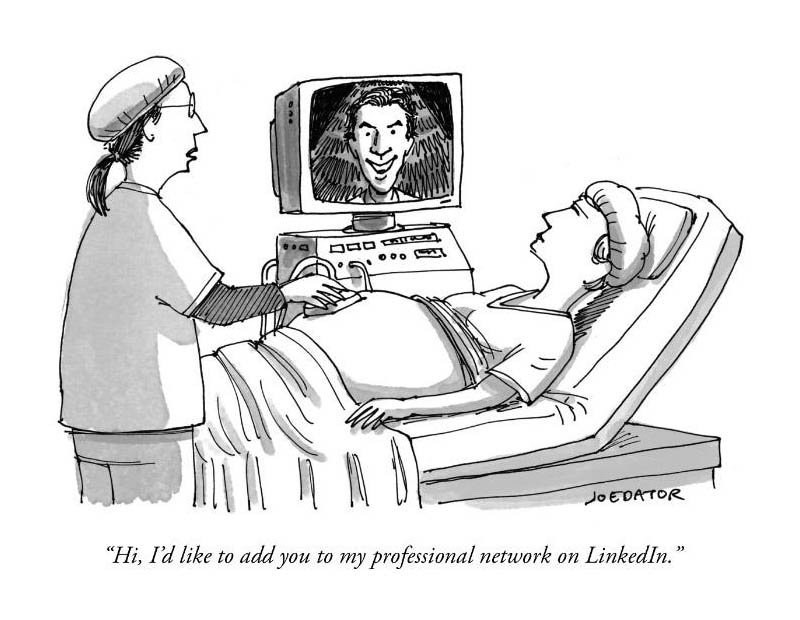

Anywho, folks demanded evidence to back up my idea, so I did what any self-respecting designer would do: I dusted off my copy of Photoshop and got to work.

Of course, nonsense loves company, so folks sent me some examples of their own. All in all, a very good day of internetting. But, there’s more, and this is where things get wild.

Later that afternoon, Robinson Meyer, a writer at The Atlantic, sees my tweets, and decides he’d like to write a blog post about my dumb idea. And how could he not? Media organizations love pot shots against other media organizations. So, later that day, I found myself on The Atlantic website:

Best of all, Meyer wraps up the article by saying: “You’re a hero, Frank.”

Whoa. I don’t have a LinkedIn account, but if I did, you bet your ass that’d go on there. Just think of it:

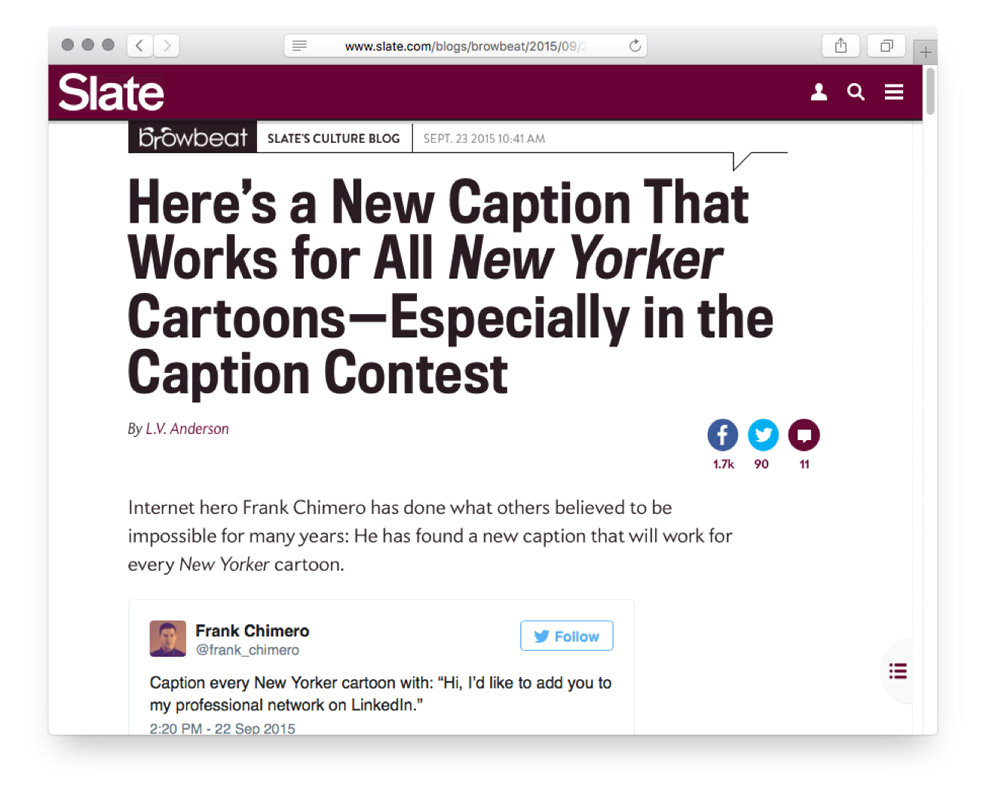

The cartoons kept moving. They were picked up by Slate. And then HuffPo. And then Time. It went viral. I don’t remember the exact number of shares and hits from Facebook and Twitter, but it is a number that seems to resemble the GDP of a small Micronesian nation. Everyone was apparently very bored at work that day. People were telling me that their dad shared the cartoons on Facebook, and before they weren’t sure if he knew of the magazine. Dear reader, we have infiltrated Dad Facebook.

LinkedIn’s ears must have been burning. Even they got in on the game:

We're partial to @Frank_Chimero's suggestion. Caption that works for every New Yorker cartoon: http://t.co/xQT2fgVArX pic.twitter.com/bHI8zLb9Ka— LinkedIn (@LinkedIn) September 23, 2015

Brands gotta brand, I suppose.

A brief aside: Many online publications have quotas for their writers, sometimes up to 10 posts per day. What does this mean? There is very little time for original writing, so staff spend most of their day rewriting the interesting posts they find elsewhere. No rewrite is ever complete, though. Small elements of language stay intact, and they can act as tracer cells which track the lineage of content.

In Robinson’s article, the tracer cell was his hyperbolic compliment. Remember? “You’re a hero, Frank.”

That sentiment stayed preserved, yet modified on Slate. Internet hero!

Might as well add that to the resume, too.

Oh, and Time beefed it up a little bit. GENIUS!

Of course that’s going in, too. Mom would be so proud.

Check, please.

I am a dedicated designer with a rigorous process. If you have been reading closely, you may have noticed that there is one great stone left unturned. So, while donning my laurels, I decided to enter the caption contest.

I hit submit and crossed my fingers.

A few days later, my Twitter account started gurgling again. Something was going on, but it wasn’t what I thought it’d be.

Ladies and gentlemen, we have infiltrated the building. Not just the building, the magazine! Here it is in all of its glory.

This went from a dumb idea I had on my commute to a real caption in the magazine in six days. Dumb fun moves fast. When I heard it was in the issue, I did what any sane person would do: I left work early and poured myself a giant glass of wine to toast my victory. I felt warm and powerful, on top of the world and maybe just a little, tiny bit drunk on attention and alcohol.

The next day, I woke up hung over and realized everyone forgot about the escapade. (Which, by the way, is precisely what they should have done.) Another New Yorker issue came out with more cartoons, and Twitter shifted its attention to the Republican debates. We moved on. Even me: as I saw friends over the next week or two, they would want to talk about “the New Yorker thing”, and I’d be embarrassed, because I forgot it happened. You can also see it here. This essay is published three months after the caption ran in the magazine. It took a day or two to write the events down, but I let it sit unfinished for weeks, feeling that the story needed to end in a pretty bow instead of dissolving back into normal life.

This is typically the part of an essay where the writer expands the scope to offer a lesson. “This is what this means. This is what we can learn.” Writing about the caption has been difficult, because there aren’t any lessons. I’m not even sure I did anything. I didn’t draw the cartoon. I didn’t write the subject line of LinkedIn’s email. I didn’t write the original captions that I took out. I didn’t write the article for The Atlantic. I didn’t rewrite it for the other publications. I didn’t even make the best cartoon with my idea! No doubt: it’s the Trojan horse cartoon. The story of my success, if it is anything, is a paean to laziness.

So what did I do? I heroically and geniusly copied and pasted some text. Do I deserve credit in the magazine for that? (For the record: the caption ran in The New Yorker without any mention of me, and I think that’s just fine.)

The compliments, of course, are purposefully exaggerated for humor, but I think they also suggest how we’re all a little uncomfortable with honoring this kind of behavior as creativity. Fun isn’t bad, but most anyone would agree that our culture gives this kind of media much more attention than its worth. (See The Fat Jew’s 7.5 million followers on Instagram.) This is disappointing and difficult to reconcile, especially when a lot of my creative friends are struggling to get their original work properly credited online. As soon as the work is introduced to the network, there’s always someone there willing to share, strip credit, and assume proxy authorship.

Then again, there’s no use wringing my hands over this. The stunt left just as quickly as it came. My secret stays safe, despite all of the attention. Because on the internet, nobody knows you’re a dog.

Special thanks to the staff over at The New Yorker for having fun with my dumb idea—especially Bob Mankoff, cartoon editor at the magazine, and Liam Walsh, who created several of the cartoons I used as examples, and illustrated the cartoon with “my caption” in the magazine.