Beyond the Machine

Creative agency in the AI landscape

This talk was given on October 14, 2025 at Kinference in Brooklyn, New York.

Spoiler alert: the last part of the talk covers plot points of the movie Spirited Away. Another warning is included right before the spoilers with a jump forward link to the spoiler-free conclusion.

I am so tired of hearing about AI. Unfortunately, this is a talk about AI.

I’m trying to figure out how to use generative AI as a designer without feeling like shit. I am fascinated with what it can do, impressed and repulsed by what it makes, and distrustful of its owners. I am deeply ambivalent about it all. The believers demand devotion, the critics demand abstinence, and to see AI as just another technology is to be a heretic twice over.

Today, I’d like to try to open things up a bit. I want to frame the technology more like an instrument, and get away from GenAI as an intelligence, an ideology, a tool, a crutch, or a weapon. I find the instrument framing more appealing as a person who has spent decades honing a set of skills. I want a way of working that relies on my capabilities and discernment rather than something so amorphous and transient as taste. (If taste exists in technology, it needs to be smuggled in.)

Thinking of AI as an instrument recenters the focus on practice. Instruments require a performance that relies on technique—the horn makes the sound, but how and what you blow into it matters; the drum machine keeps time and plays the samples, but what you sample and how you swing on top of it becomes your signature.

In other words, instruments can surprise you with what they offer, but they are not automatic. In the end, they require a touch. You use a tool, but you play an instrument. It’s a more expansive way of doing, and the doing of it all is important, because that’s where you develop the instincts for excellence. There is no purpose to better machines if they do not also produce better humans.

I believe artists have more helpful things to say than the money guys about how to use and creatively misuse technology. So today, I want to share four artists, and I hope you’ll leave with some more flexibility in how to collaborate with the machine in your own work, creative or otherwise.

First, some background. Over the summer, the vibe around AI seemed to shift.

All those aggressive predictions about the destruction of knowledge work didn’t hit their six-month deadline. The much anticipated GPT-5 felt more like an incremental step up from GPT-4, signaling LLMs have probably moved past the revolution phase and into optimization and evaluating trade-offs. The fact that OpenAI is encouraging everyone to fantasize about hardware with the Jony Ive annoucement tells me the software side may not have enough headroom for the profits they need. Meanwhile, small, local models are good enough for a surprising number of use cases, while being cheaper, more private, and energy efficient.

Progress has slowed, projections are being walked back, and the science is starting to look more hazy. We may not be in AI winter, but I am hoping for an AI autumn. Autumn is amazing; the air cools, the mania of summer dissipates, things slow down. Right now, the changes in AI feel incremental enough to start laying down strategy. This means we can think about our approach with steadier footing instead of vacillating in response to the hype, whether it comes from the top as LinkedIn posts by prepper CEOs or from the bottom by the hustleheads on X.

The hype is expected—new tech runs on speculation. You can feel the residue of the last 30 years of booms. There is a sense that people missed their chance to get rich on the internet, on ecommerce, on the app store, on social media, on crypto, on meme stocks, on NVIDIA. The hype bubbles get inflated because individuals don’t want to miss their chance at another windfall, and companies don’t want to get displaced by any nascent technological shifts. The history of tech has calcified into stories of dramatic wins and unforeseen downfalls, and what results is a tech culture of near compulsory participation in prediction rather than creating value or serving needs.

The TV show The Wire had a phrase about how people navigate the risk of failure inside more traditional institutions: “You can’t lose if you don’t play.” In the tech world, the logic reverses. The drawbacks of a collective fallacy are smaller than not participating in the next innovation, so the rule becomes, “You only lose if you don’t play.”

In other words, the push to join the AI rush comes from the sense that it’s the only game in town right now, and everyone else is already playing. The hype gets louder, and the bubble gets bigger.

What surprised me wasn’t the AI hype, though, but the lack of solidarity that came with it. Faced with the story of AI labor displacement, our first instinct as technology workers wasn’t to protect one another, but to search for ways to use the tools to replace our collaborators.

The fractures fell neatly along disciplines: engineers using AI to wish away designers, designers wishing away engineers, product managers wishing away both. In this climate, AI becomes frenemy identification technology, another way to avoid working together. It’s always easier to grab a tool and bypass the mess of coordination, even if that means doing more and doing it alone. AI lowers the barrier to working outside your lane, and sure, that could mean more overlap between disciplines, but right now, we’re mostly boxing each other out or stepping on one another’s toes.

With collaboration already strained, it’s no surprise that we fall back on individual effort. But individual work, disconnected from the whole and accelerated by automation, only makes the turbulence worse and the course corrections more violent. The deeper problem is that companies still haven’t figured out how to mass-produce orientation, so workers get thrashed around in the speed and scale of the system.

When coordination breaks down, the fantasy of self-sufficiency rushes in to fill the gap. GenAI, after all, is built as an individual technology, whether it is expressed as a one-on-one chat, the fantasy of the one-person startup, or the sycophantic assistant set up to glaze you. It says “just get it done, no skills needed.”

All you need is a prompt, a dream, and some vibes. And, of course, we’ve chosen an individual to be the face of that.

“Money is everywhere but so is poetry. What we lack are the poets.”

Federico Fellini

Vibe coding has a mascot, and it is the music producer Rick Rubin. A bit of background on him before we get back to vibe coding.

Rubin got his start in the music industry as the co-founder of Def Jam Records. He helped bring hip-hop into the mainstream by producing records for LL Cool J, Run-D.M.C., and the Beastie Boys. Later, Rubin produced albums across genres for Jay-Z, Johnny Cash, Red Hot Chili Peppers, and plenty of others. He’s credited with shaping the sound of the last forty years without ever learning to play an instrument. In interviews, Rubin leans into the irony: he can’t operate the board, can’t engineer, can’t really play a guitar.

Rubin’s supposed lack of technical skill has made him an easy fit as the poster child for vibe coding, the notion that with the right sensibility and some prompting, you can steer technical output without ever knowing how to use the tools.

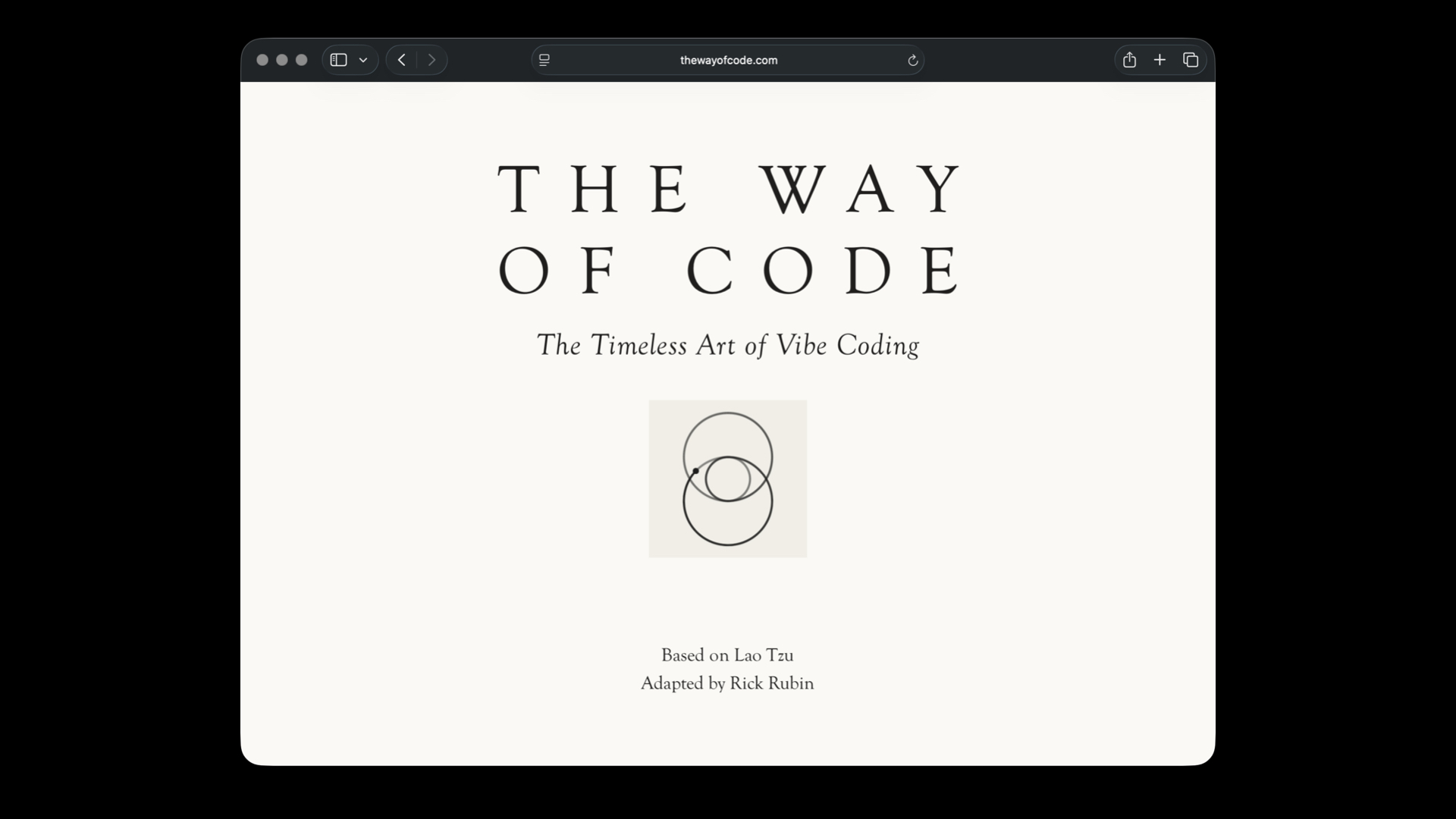

Anthropic played into this with The Way of Code, a project where Rubin rewrote the Tao Te Ching, an ancient Chinese philosophical text, to be about vibe coding.

It was a marketing stunt, but I read it as a proposal that the path to enlightenment is moving away from competency and towards the vibes.

Here’s one of the chapters from the site:

The Way of Code #47

Without going outside,

you may know the whole world.

Without looking through the window,

you may see the ways of heaven.The further you travel, the less you know.

The more you know, the less you understand.Therefore, The Vibe Coder

knows without going, sees without looking,

and accomplishes all

without doing a thing.

Ugh.

When I first saw this, I thought “Did anyone read this?” That’s always the question when encountering something that you think is god awful. But in the AI era, I found myself asking a follow-up question: “Did anyone write this?”

It’s a complicated knot. Art is interesting partly because someone put effort into making this thing, not all the others they could have made. But artists also know that the best ideas can appear whole, as if they made themselves. Effort isn’t what makes the work meaningful, yet it still feels like a small violation to release an AI’s output untouched.

I figured they used AI to write revised chapters of the Tao since the verses are shown beside some vibe coded visuals. But in interviews Rubin says he wrote them himself. I’ll be generous and say that it’s a joke that doesn’t land for me.

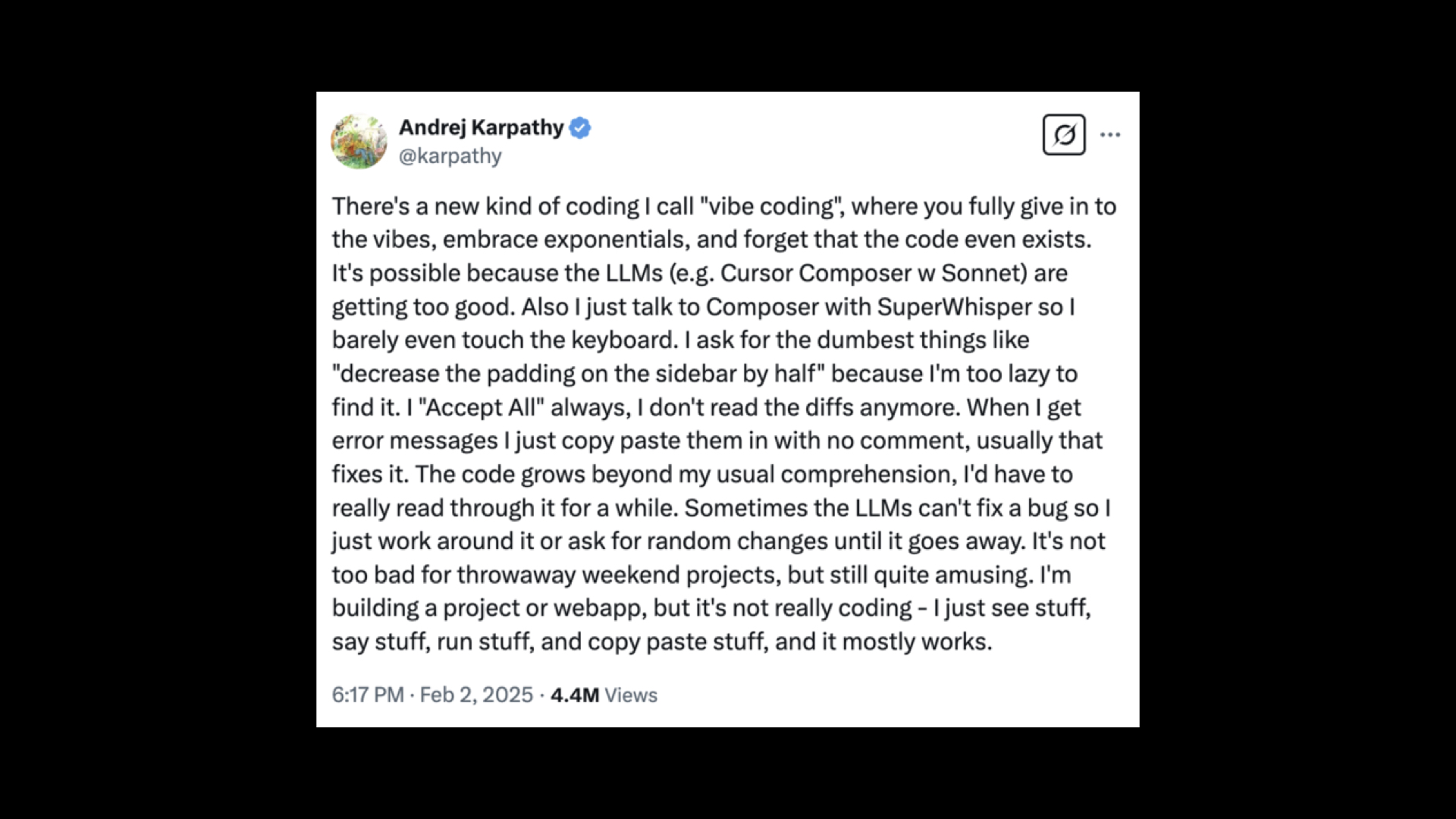

Like most ideas that spread like memes, “vibe coding” got carried way too far. Karpathy’s original post was modest: a fun hack for engineers, and “not too bad for weekend throwaway projects.” Lightweight, bounded, disposable work, perfect for prototyping, experiments, scripting, and personal software. If this is the scope, I’m on board, giddyup.

But once the phrase caught on, people started applying it everywhere, stretching a hack into a philosophy worthy enough to be inserted into ancient texts.

Like a lot of things with AI, it feels completely out of proportion. Maybe that’s the humor of it. But in the process, Rick Rubin became valorized as proof you don’t need skills. It’s as if wu wei, the principle of not forcing at the heart of the Tao, had been hollowed out and recast as dependency. Use the machine, no skills or knowledge needed.

Rubin obviously has skills and knowledge, but we get two Rick Rubins. There’s the one in the studio, unable to play guitar, but gifted at guiding artists and clarifying what they want. And then there’s the cartoon Rubin, who leans into his lack of ability in interviews, writes bad poems, and poses as the guru. Maybe that split is what happens when the work becomes too abstract from execution.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about my use of AI as a kind of spatial relationship. Where do I stand in relation to the machine—above it, beside it, under it? Each position carries a different kind of power dynamic. To be above is to steer, beside is to collaborate, below is to serve.

In the Rubin vibe arrangement, you’re under the machine and dependent on it. Without skills, the model’s limits become your own, no different from anyone else typing wishes into a text box. Take what the AI gives without question and you’re not producing, you’re consuming. Eventually, that passivity gets used against you. We’ve seen it before: streaming services flattened art into algorithmic averages and background noise, newsfeeds rewired attention toward outrage because engagement meant growth. Each time, the machine attracted us with individual customization while quietly taking control of the terms. The same will happen with AI if used for passive consumption, even if that consumption is dressed up as execution.

So while vibe coding may be useful for short-term work, it’s not a suitable approach for anything intended to last longer than a tub of yogurt. Time saved is not strength gained, so I went looking for other examples about how to work with the machine.

“It could be uplifting to watch a person energetically building a beautiful coffin. And depressing to watch someone sloppily and carelessly make the worst birthday cake ever.”

George Saunders

I’ve spent the last couple of months digging into Brian Eno’s work and music.

Eno began as a keyboardist in the band Roxy Music in the early ’70s, helping to popularize the use of synthesizers in pop music. Then he went solo, and later built a career producing some of the most important bands of the last fifty years—David Bowie, Devo, Talking Heads, U2, and, more recently, collaborating with Fred Again.

Eno is rarely the virtuoso; instead, he’s the collaborator, the systems thinker, the one who turns the studio into a laboratory. What makes Eno especially relevant for me is his work beyond the songs. His impact as an artist has mostly been to define new forms, supply vocabulary, and arrange the vibe.

In the late ’70s, Eno named ambient music and, in doing so, changed how we think about what recorded music does by creating compositions fit for purpose and place. Music for airports, music for walking, music for thinking. Above is an in-browser recreation of track 2 on Eno’s Music for Airports by Tero Parviainen.

Rather than a pre-arranged composition, his music drifts and breathes, built from overlapping loops of different lengths that phase in and out of sync with one another, creating slow variations he can’t fully predict.

Eno called it “a river of sound,” always the same and never the same. In that sense, ambient music was his first experiment with what he’d later name generative art: systems that grow and change within carefully set constraints.

Since the ’80s, Eno has been interested in using software and systems that produce music and visual art. In the last decade, he carried this idea into the phone with generative apps for music-making.

- Bloom lets you seed melodies by tapping dots that ripple outward.

- Scape has you place abstract elements into a pictorial landscape to create a landscape of sound

- And Reflection dissolves the boundaries of a Brian Eno album by shipping generative software that allows endless music.

I believe that if you’re looking for a music producer to give some inspiration on how to work with machines, you’d have better luck and more ideas to consider with Brian Eno than Rick Rubin. The difference, to me, comes down to placement.

If working in the Rubin style puts you under the machine, Eno works beside it. He sets up a system with his inputs and samples, then listens, selects, and continues to shape. Eno often says while making music he feels like a gardener: planting loops and textures, then watching them sprout into something unexpected with the potential to become incredibly beautiful with a little bit of care and pruning. The machine may produce material, but the job of shaping it into something meaningful still rests with him. It is creativity as cultivation.

The value of the machine’s output depends on how we see it, and our interpretation often has little to do with its technical perfection. A flawless, virtuoso output from GenAI can feel lifeless, while something raw or broken might have something interesting about it. That’s why I like to write bad and contradictory prompts, because they feel like they are more aligned with how these models actually function. The models aren’t deterministic; we don’t fully understand how their associations form or why certain patterns appear. So why not let them drift into ambiguity and see what happens? I wouldn’t want an irregular AI in my bank app, but in a creative workflow, hallucinating feels like the point of it all.

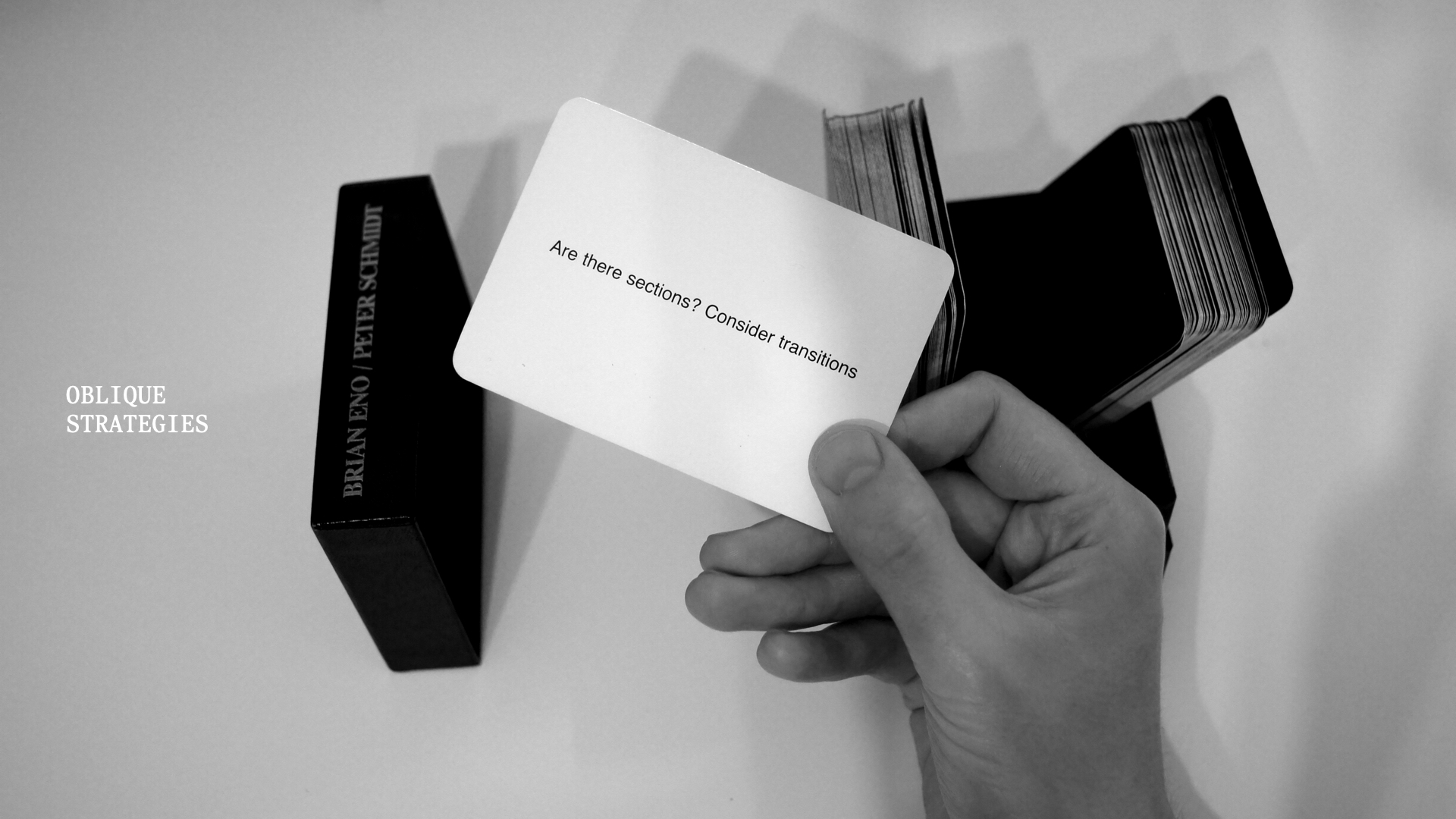

In a sense, Brian Eno was tinkering with prompts long before we had the word. In 1975, he and Peter Schmidt created Oblique Strategies, a deck of cards meant to shake artists out of their habits. Each carried a short phrase to be interpreted and followed: “Honor thy error as a hidden intention.” “Use an old idea.” “Work at a different speed.” These weren’t instructions so much as provocations—small reframings that opened space for something unexpected to emerge.

That, to me, feels like a better model for prompting in creative work, whether the first act of execution belongs to a person or a machine. A good prompt doesn’t need to function like a blueprint. They can also behave like a horoscope or a fortune.

The results from ambiguous prompts can be weird, illogical, and incredibly stimulating, because the system is not scared of being wrong. The good stuff is at the technological edge, even if it’s a bit shit. Eno put it beautifully in 1995:

“Whatever you find weird, ugly, uncomfortable, and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature. CD distortion, the jitteriness of digital video, the crap sound of 8-bit, all of these will be cherished and emulated as soon as they can be avoided.”

Time has proven him right. This idea explains the return of vinyl, the revival of iPods, Gen Z filming parties on old digital camcorders, or why 8mm film is nostalgic for Boomers in the same way the blown-out photos from the first iPhone make us Millennials sentimental. And if I had to make a guess, we will miss the awkward trickle-in of words seen in modern LLMs.

In other words, every new technology promises better clarity, yet its essence is determined by the noise it produces. The friction of limits is what gives a technology its character, so when a system becomes too smooth, too all-encompassing, or too accommodating, it stops having a signature at all. Here’s Eno again from earlier this year:

“I can see from the little acquaintance that I have with using AI programs to make music, that what you spend nearly all your time doing is trying to stop the system becoming mind numbingly mediocre. You really feel the pull of the averaging effect of AI, given that what you are receiving is a kind of averaged out distillation of stuff from a lot of different sources.”

An average email or line of code is fine. Average art isn’t. To make something alive with AI, we have to resist its pull towards average by working beside it, shaping what it gives, and listening for what’s missing. Sometimes what’s needed is a good, old-fashioned mistake or two.

Another answer is not to cultivate the machine’s output but to compose through it, treating the model as material, choosing the inputs and shaping the rules. In other words, not working beside the machine, but stepping inside it.

“By the late twentieth century, our time, a mythic time, we are all chimeras, theorized and fabricated hybrids of machine and organism.”

Donna Haraway

If Brian Eno shows us what it means to work beside the machine and cultivate its outputs, Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst show us what it means to move into it.

Herndon and Dryhurst are visual artists and musicians who, for over a decade, have worked with AI and treated digital systems as instruments for rethinking music itself. They’ve built tools and trained models that show what AI can offer creative practice as a means of integration, extension, and amplification of the artist.

Consider Proto from 2019, in which they developed an AI “baby” named Spawn. They trained it with live performance using call-and-response with singers, then used the model as a vocal instrument in a later released album of the same name.

They’ve founded Spawning, which they call the consent layer for AI, letting artists decide whether to opt in or out of model training. Alongside it, they launched a beta for Public Diffusion, a foundation model trained entirely on 30 million public-domain images, designed to make generative work copyright-safe.

Then there’s xhairymutantx from 2024, shown at the Whitney Biennial, a project where they trained a text-to-image model on photos of Holly, then opened it to the public, inviting others to create with it and explore how identity becomes warped and extended inside generative systems.

And most recently, they created The Call, a choral AI project involving choirs across the UK, where recorded voices become a shared dataset, and the resulting models are folded into a spatial audio installation performing generative choral arrangements. Serpentine Gallery acts as steward of a data trust that governs usage, ensuring the participating choirs are paid and have agency over how their voices are used.

The compositions are inspired by Medieval music, Renaissance music, and hymns. The vocal performances were made from a combination of the choral data and Holly’s own song data. Let’s listen for a minute:

One of the things you notice when encountering Herndon and Dryhurst’s work is that they are just as concerned with the administrative structures needed to serve artists as they are with the creative potentials of new technology. They say that all media is training data, so their work wrestles with the implications of what media generation at scale means for artists. The AI model and the economic model don’t need to come packaged together. Both can be areas for innovation, and severing the implied connection may be a requirement for ethical AI.

What emerges from this approach isn’t just art, but a reimagining of the conditions that make art possible. When the system is designed to respect artists, scale becomes a tool rather than a threat. It opens up new questions. What new forms appear at that scale? The story can be rethought; instead of fewer people making the same amount, what about the same number of people making stranger, more abundant, more connected work?

As the tools evolve, the metaphors we use to understand them must also be updated. Herndon and Dryhurst describe this next phase as the move from sampling to spawning. Sampling was the logic of the 20th century. You took a slice of a record—a James Brown breakbeat, a horn stab from a jazz LP—and folded it into a new track. It was transformative, but you knew the source, and you could trace the lineage.

Spawning is different. Instead of lifting fragments, you train a model on an artist’s entire body of work and generate new material in their style. Clear lineage, but fuzzy origins. Sampling dealt in citation. Spawning touches the DNA. This distinction matters because spawning raises the stakes in ways that sampling never did. When your work trains a model, what’s taken isn’t a note or a beat, but the sensibility and perspective of your practice.

Sampling sparked arguments about ownership and credit; spawning resets the terms. The internet challenged copyright by creating infinite distribution of perfect copies. With AI, what happens when infinite distribution is hooked up to infinite imitation?

You’re so wonderful

Too good to be true

You make me, make me

Make me hungry for you

Why Can’t I Be You? by The Cure

I opened this talk with a tone-deaf marketing moment from an AI company, so it feels fitting to end with another. Last March, OpenAI launched image generation in ChatGPT and encouraged people to upload selfies and turn themselves into anime characters.

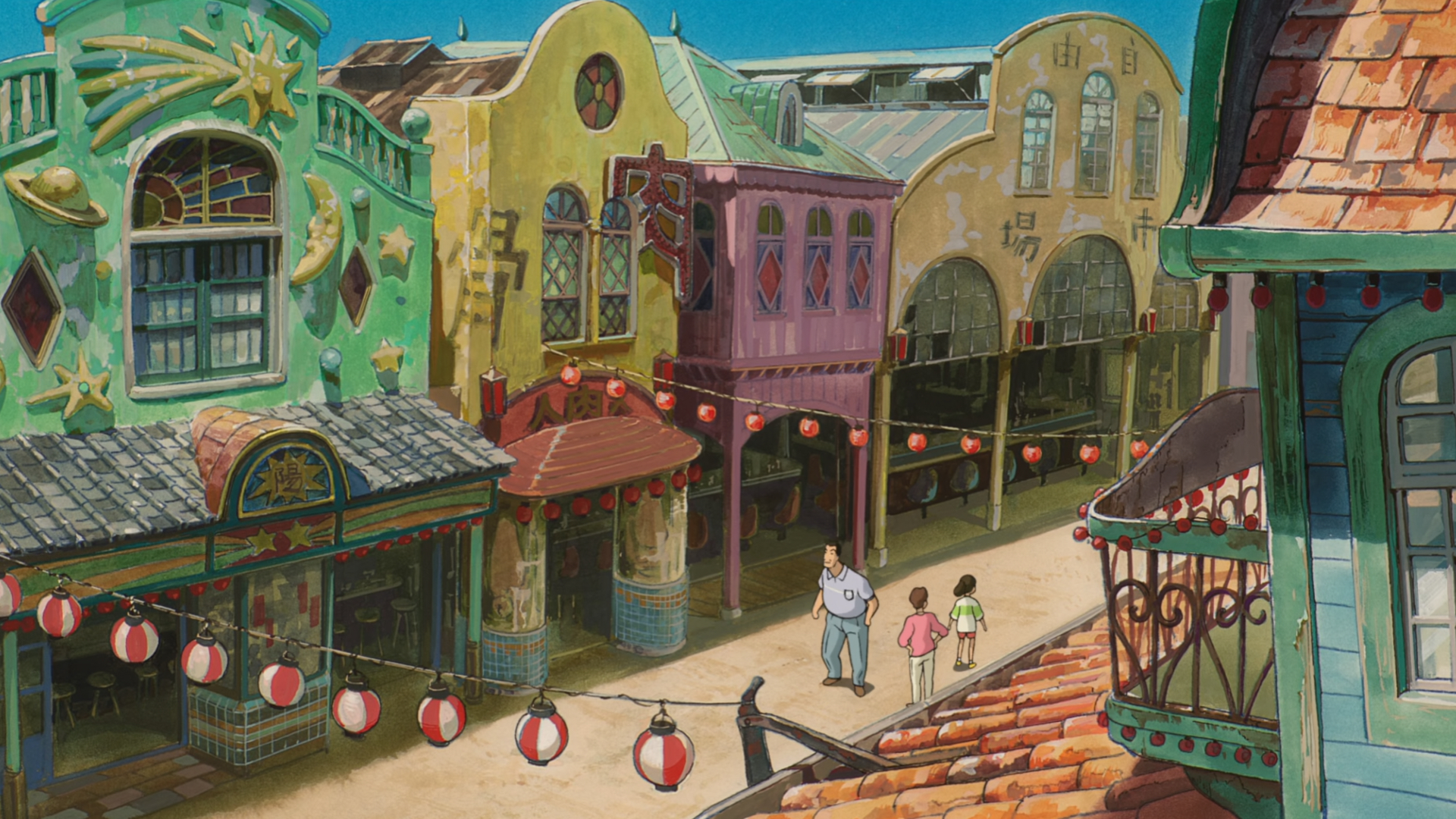

The results were unmistakable: the soft light, round faces, and watercolor skies of Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli. Within hours, social media flooded with Ghibli-fied images—sweet, strange, and grotesque.

The irony cut deep. Miyazaki’s films are animated by hand. They require over 150,000 drawings per movie, and now his studio’s style was being used to sell the very shortcuts and automations he’s spent a career standing against. The model ate Miyazaki’s work along with everything else, so OpenAI can puppet his style when it suits their needs. Last year, they took Scarlett Johansson’s voice to promote text to speech. Next year, they’ll line up a new artist.

Enough has been said about the viral moment at this point, so instead of staying with the style discussion, I want to value Miyazaki’s art and think about the substance of his movies.

To finish the talk, I’d like to take a look at Spirited Away, a film that wrestles with identity and imitation, appetite and satisfaction. While there’s always a risk in reading too much allegory into art, it seems fair to seek wisdom in what moves us.

Spoilers for Spirited Away after this point.

Jump to after the spoilers.

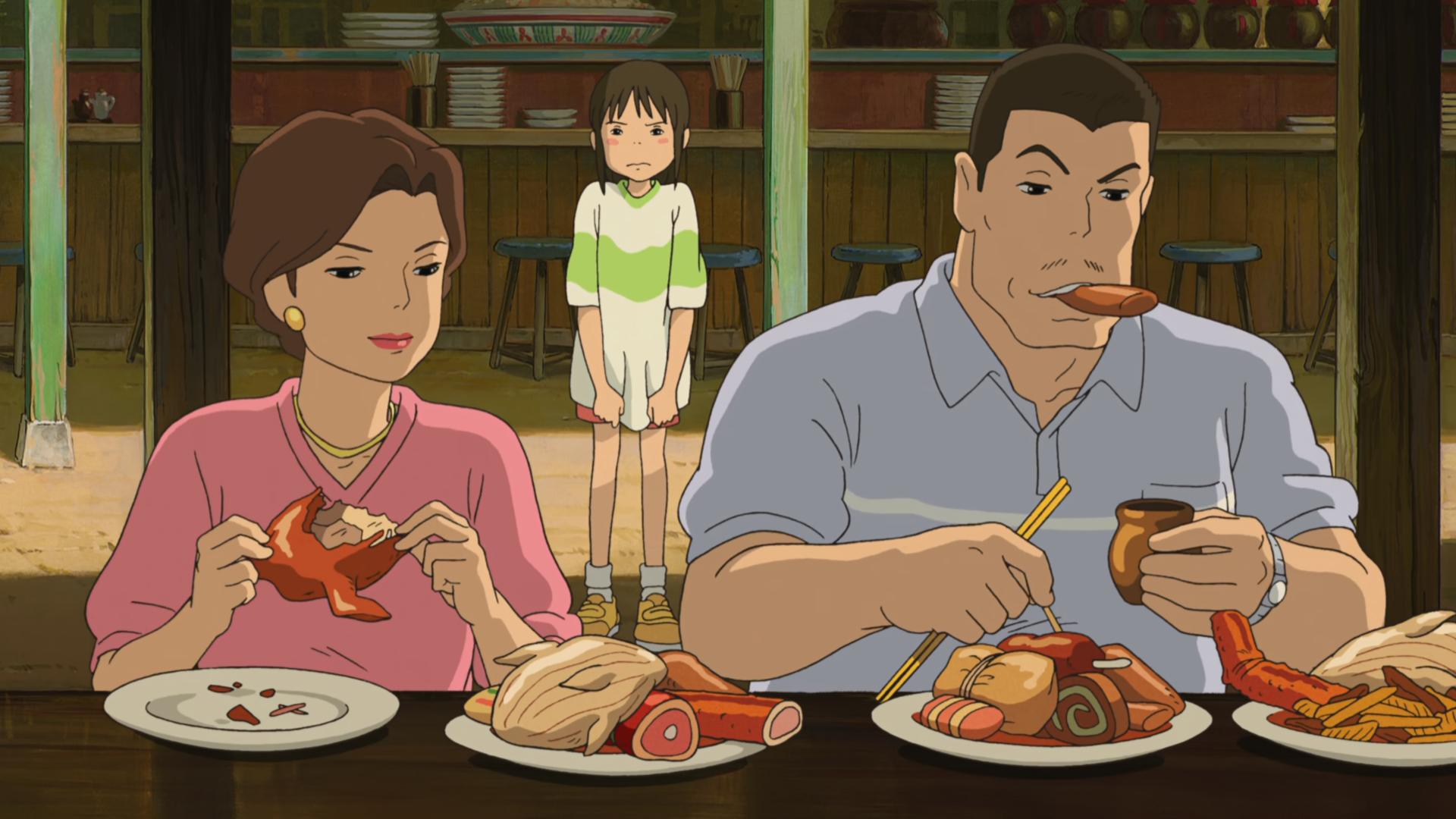

Spirited Away begins with a crossing. Driving through the countryside, Chihiro, a ten-year-old girl, and her parents pass a torii gate, a marker used to signify temples.

They park and wander into what looks like an abandoned amusement park. Chihiro and her parents don’t realize it yet, but the torii gate they passed marked a threshold. They’ve entered the spirit realm.

When they find an unattended food stall, her parents sit down and eat, promising to pay later. But the food isn’t for sale; it was prepared as an offering for the gods. They take what isn’t theirs, and in doing so, Chihiro’s parents fail the moral test.

As punishment, they are turned into pigs. The parallel to AI is hard to miss: eating without consent, where uncontrolled appetite destroys any awareness of the intangible dimensions of what’s being consumed, etc. etc. etc.

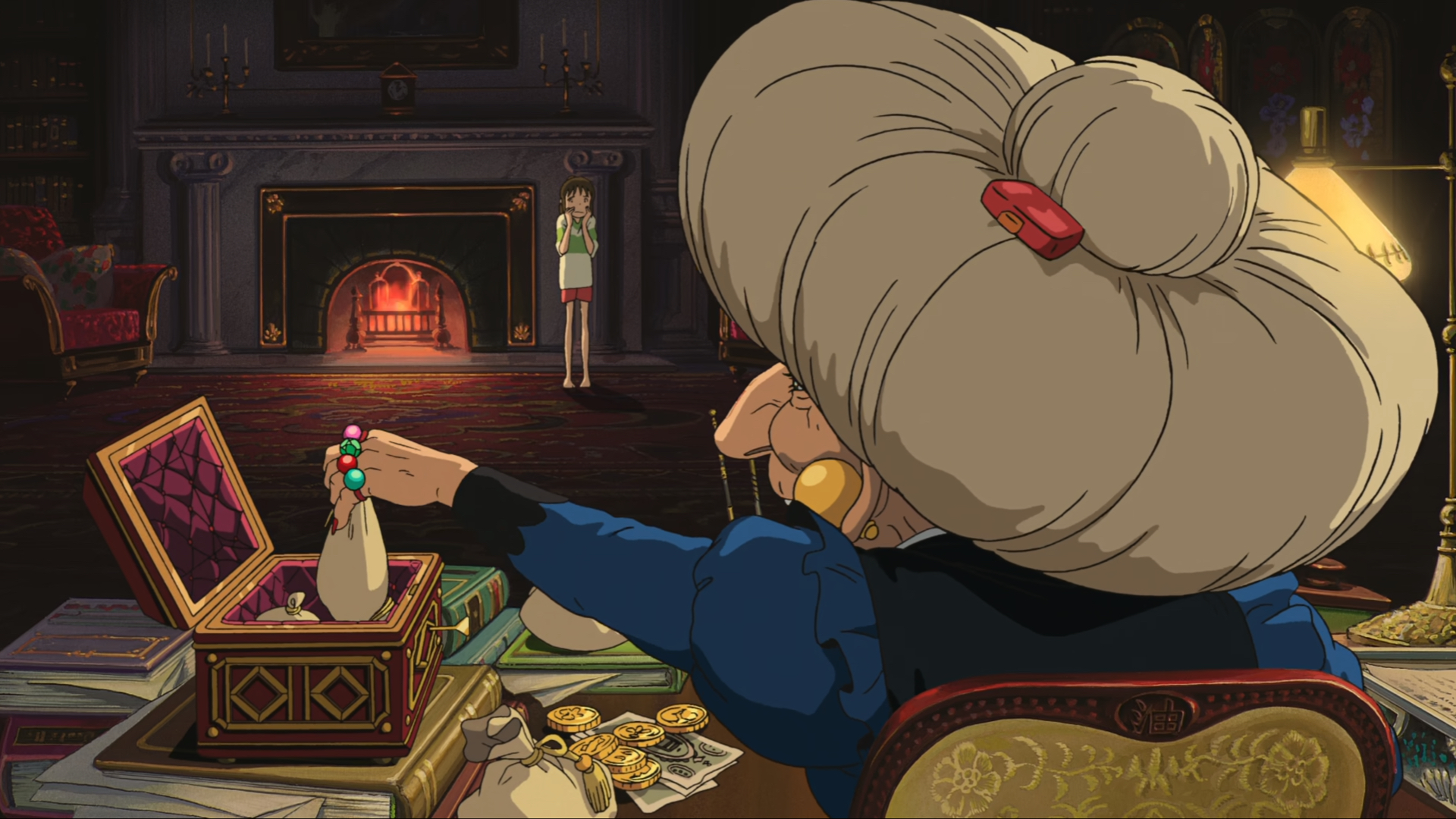

To save her parents, Chihiro is told to take a job in the nearby bathhouse. It’s a greedy place that runs on pleasure and appetite; ostentatious and opulent in every way. It is managed by Yubaba, a witch who binds her workers to service by stealing their names.

Chihiro is renamed Sen (translation: thousand, literally a number), and learns that if she forgets her true name completely, she will never find her way back home. The lesson is clear: in a place ruled by appetite, everything can be eaten, even who you are. A similar pattern happens with the models: once they eat your work, they take your name off of it to use your labor for their own purposes.

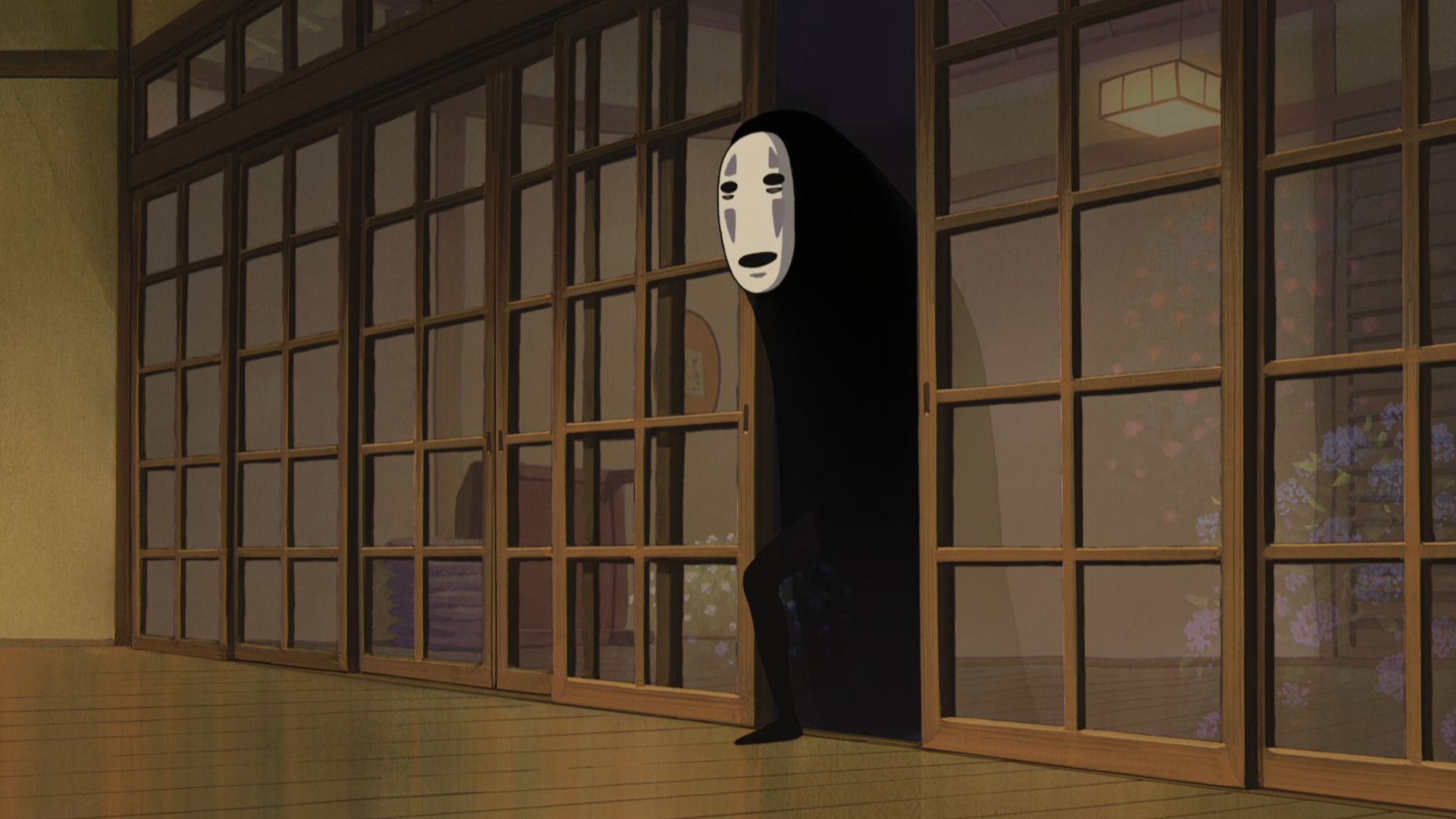

The movie later returns to hunger, this time in its spiritual form. Chihiro meets No Face, a quiet spirit waiting outside the bathhouse in the rain. Out of kindness, she lets him in to take shelter, not realizing what she’s invited inside.

No Face is mimicry embodied. Once inside the bathhouse, he observes and absorbs its values. He tries to find ways to repay Chihiro for letting him into the bathhouse, but she turns down his offerings.

Later that evening, a greedy frog who works at the bathhouse sneaks back to the Big Tub to see if any gold was left behind by another customer. While searching, he comes across No Face.

No Face lures him closer by materializing gold from his hands because he sees that the frog wants it. The frog is captivated, and steps forward. He’s entranced. The frog gets closer,

and No Face eats him. He can now speak in the frog’s voice, because consuming allows him to mimic and command. But No Face is still hungry.

Another employee comes along after hearing some noises. No Face uses the frog’s voice to issue commands to the next employee in line. He’s says he’s hungry. Wake everyone up. It’s time to eat. So he produces more gold, gets more food, and his appetite continues to escalate.

It’s not hard to see the parallel, is it? An insatiable force, feeding endlessly to imitate, provoking action with vast sums of money?

No Face’s hunger hooks into the bathhouse’s greed. Word spreads that a wealthy guest has arrived, and the place erupts into a frenzy to serve him.

Cooks parade steaming platters through the halls, servants sing and dance for his attention, even Yubaba eventually takes notice. Everyone wants a piece of No Face, but no amount of food or flattery can satisfy him. What No Face wants is to see Chihiro.

There’s something poignant about how he keeps trying to give her things, because that’s what he’s learned gets people’s attention.

But Chihiro keeps refusing, which both frustrates him and feeds his obsession with her.

No Face’s consumption eventually comes to a head. He eats two more employees and wrecks the joint, so Chihiro is forced to confront him.

No Face does not understand that what he’s really seeking—genuine connection—can’t be bought or consumed. He mistakes his spiritual hunger for a physical one, trying to feed an emptiness that food can’t fulfill.

When Chihiro refuses No Face’s gifts for the last time, she offers up herself to be eaten. But first, she wants No Face to eat the medicine she had been saving to restore her parents.

No Face eats it simply because he eats everything. And suddenly, the intoxication of the bathhouse begins to break.

The bathhouse workers finally see his gold as fake, No Face vomits up everyone he ate, and he quickly returns to his mute, shadow thin form.

I suppose the lesson is that you can’t get enough of what you don’t need.

On her way out of the bathhouse, Chihiro sees No Face brought back down to size. She realizes what he needs is connection, and lets him follow her as she leaves.

No Face joins Chihiro on the train to go meet Yubaba’s gentle twin Zeniba in the swamp.

Zeniba is Yubaba’s opposite. Warm, less ostentatious. At Zeniba’s cottage, something shifts. After knocking, No Face hesitates at the door, but she holds it open for him to enter. This time, he’s invited in.

There No Face receives something that finally satisfies him. He can eat normally now that he has a modest place to belong without the performance of abundance.

No Face finally finds peace by spinning thread beside Zeniba, turning his attention to small and steady work to make the materials for a collaboration.

The lesson for AI might be similar. Its danger comes because it operates inside systems with no sense of “enough.” AI needs boundaries, and so do we. The question isn’t just “what can this machine do?” but “what should it serve?” and, most importantly, “when should we stop?”

Listen, I’m not naive. I know how little room there is to move inside these systems. It’s 2025, and I’m tired. I don’t believe words like these will change much. The people who could change things aren’t listening, and the incentives are too strong to keep the machine running.

So I look for something smaller: incremental progress, unexpected benefits, minor redirections, small refusals. I am not sure how to feel about it, which is why I am trying to be articulate in my confusion. I want to carve out a small creative place for myself in everything that is happening. Is it possible?

The optimist in me remembers Chihiro, the girl who brought the devouring spirit back down to size with her refusal. The pragmatist in me remembers Miyazaki, the artist who made her, still caught in the machines he tried to resist. The realist in me knows that whatever I see in them is coming from me.

There’s a quote by the philosopher and writer Simone Weil that I keep with me. She says:

“We have to endure the discordance between imagination and fact. It is better to say, ‘I am suffering,’ than to say, ‘This landscape is ugly.’” Simone Weil

In other words, it is better to stay with your own experience instead of projecting it outward.

Spirited Away was released in 2001. It has nothing to do with AI. If I gave this talk at a different time, No Face could have been crypto, could have been Google, could have been social media. Allegory has its limits. Simone Weil might say that what all these interpretations have in common is that I’m the one making them.

I used to like technology. The only reason it frustrates me is because I secretly believe it can satisfy me. Perhaps it once did, but the machine is not enough. Is that technology’s failure or my own growth? There are better things to suffer for.

Maybe writing this is my own version of finding some small work to do at Zeniba’s cottage. The wheel spins and I put another few lines down on the page. And I think, “the machine may know everything, but at least I know where to stop.”

It sounds like something from the Tao. Which leads me back to Rubin’s adaptation. I was unfair earlier. Not every verse he wrote is bad. If you dig, there is one hidden in the middle of the stack:

The Way of Code #53

The great way is easy,

yet people search for shortcuts.Notice when balance is lost:

When rich speculators prosper

while farmers lose their land.

When an elite class imposes regulations

while working people have nowhere to turn.

When politicians fund fraudulent fixes

for imaginary catastrophic events.All of this is arrogance and corruption.

And it is not in keeping with Nature’s Way.

Again, I wonder: did anyone read this?