Beyond the Machine Extras

Swollen appendices

Every talk leaves a lot of scraps, and Beyond the Machine is no exception.

I read a couple books, watched about 20 hours of interviews with Brian Eno, listened to 10 hours of podcasts with Rick Rubin to make sure I wasn’t being uncharitable. (One podcast was a discussion between Rubin and Eno. A really nice listen!) I clocked some serious headphone time with Holly Herndon’s discography, which I’m eager to do again. Listening to all three of her albums in one big gulp was a trip.

There were a few ideas that never grew into full thoughts, and a couple more that were cut for length. So consider this a supplemental post, an appendix of sorts, to share the leftover fragments and side paths that didn’t make it into the main piece. I’m sharing this for a couple reasons: partially because I am so intrigued by some of the ideas that were cut, and partially to show why I do these talks so infrequently. They are a lot of work.

On to the swollen appendices.

Perhaps a superficial place to start, but whatever:

AI: an ugly looking set of letters. Sounds ugly, too. Ayyy-eiiigh. Woof.

I’d be much happier if we used words like “generative models” instead of AI or GenAI. Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst from the talk have used the phrase, “common intelligence,” which is also nice, since the synthesis is only available if derived from all the work of humanity so far. Almost any name for this generation of technology is better than AI to me.

The old nut is that our current instantiation of AI is neither A nor I, and past technologies presented as AI eventually settle into a more descriptive name once the boundaries of its utility are found (symbolic reasoning, speech recognition, OCR, machine vision, machine learning, and so on). Let’s hope this happens, whether it’s LLM, GPT, or something else.

In my view, capital expectations are both the life and death of generative AI. Most of the dizzying talk around AI’s promise and peril isn’t meant for ordinary people, it’s aimed at investors and executives who need to justify the bet. They’re also the most likely to fall for it, because AI sounds appealing in the high-up abstract, but its flaws become obvious in the down-low specific.

In a funny way, it’s a bit like any other enterprise software purchase: you’re selling to leadership and navigating around the skepticisms of the people who will actually be using the software. When you’re close to the work and trying to use these tools, you become painfully aware of their benefits and limitations, and the mindful critics understand what piece of the problem comes down to tooling and what challenges are produced by people or systems resistent to change that AI can’t touch.

The first draft of the talk referenced a blog post that I love, called, “Reality has a Surprising Amount of Detail,” by John Salvatier. Here’s how I see the connection: the moment you begin the doing, what looked simple in the abstract unfolds into surprising, significant detail. Those details have real, material consequences to the work. We often get stuck or frustrated because our tools fail to account for the existence of these irregularities, where reality refuses to conform to perfect abstractions and predictions.

AI, in my use, often falls into this trap, and to a degree, so does bad management. The two lock together naturally because when done poorly they share the same point of view, which is to discount the real and specific in favor of the ideal and abstract—basically to reject the ground-level facts to inch closer to “done” or “mission accomplished.” (This is all still rough, and not kindly phrased, hence me removing it from the talk.)

In other words, largeness, whether it is big organizations or large language models, are distanced from reality due to their size, and this size and distance can make care (that is, attending to the individual qualities of a situation) an impossibility. For example, stealing 10 books is theft, but stealing 10,000,000 books is training.

If the talk wasn’t so strongly tied to music, I would be tempted to devote a section to Wendell Berry—advocate for the small, the specific, the local—to serve as a counterpoint and potentially provide words for those abstaining from AI.

Here’s Berry evaluating the dangers of scale and abstraction when it comes to ecological preservation:

The question that must be addressed, therefore, is not how to care for the planet, but how to care for each of the planet’s millions of human and natural neighborhoods, each of its millions of small pieces and parcels of land, each one which is in some precious way different from all the others. Our understandable wish to preserve the planet must somehow be reduced to the scale of our competence—that is, to the wish to preserve all of its humble households and neighborhoods.

Wendell Berry, Word and Flesh

Care and specificity go hand in hand, and our ambitions should be reduced to the scale of our competence.

I’m not well-read on Berry, so there are probably better quotes that more directly drive at this idea. It also may be completely disrespectful to include him in this whole charade. This seemed the most likely conclusion here, so I didn’t probe too deeply. Joan Tronto also has scholarship about care from a global perspective, but I dropped that line for similar reasons. If I had another 30 minutes to speak and another 2 months to research, maybe.

Back to Salvatier. In his post, he tells a story about cutting a stringer for a set of stairs (the diagonal piece that runs between the two floors being connected). He tries trigonometry to calculate the dimensions of the wood instead of tracing the cut by hand. The math is neat, but the world isn’t—wood warps and floors aren’t perfectly level. Experience in the doing tells you to always trace the cut because of these details, even if you know how to do the math.

In other words, because reality has a surprising amount of detail, it also contains the feedback mechanisms that keep us honest. Abstractions don’t. Fabrications don’t. And simulations definitely do not. When you rely too heavily on models designed to flatter and reinforce rather than correct, you lose contact with that feedback and drift into dead ends you can’t see until it’s too late.

One example I picked out (a personal pet peeve) is when designers mock up brand touchpoints on things like billboards using unprintable colors. Purples, limes, and saturated blues look great on a screen but can’t exist in the physical world using the standard CMYK inks used for most print production. The simulation of the Photoshop mockup never provides the reality of production to invalidate the creative choice. Without a knowledge of how things really get made, a designer may be seeking approval for an impossibility.

AI brings this faux reality to text and therefore all the other modes of communication, and risks reproducing the same disconnection across disciplines—spinning out unactionable strategies, vague product specs, and feedback that sounds intelligent but has no meaning. This kind of empty verbiage and posing isn’t new, but AI increases the volume of it and the ease of producing it. It lets us stay sheltered in abstractions for longer, and postpones the moment when reality pushes back, which only leaves less time to respond and raises the stakes of course-correcting.

One mark of expertise is knowing how to make something with substance. Another is being able to identify when something that seems substiantial is, in fact, empty. A lot has been made about how the models hallucinate. A more descriptive term might be “bullshit,” using Harry Frankfurt’s definition, where there is a total disregard for truth, and words have been emptied of all informative content. Bullshit existed at an industrial scale before AI, of course, AI just makes it easier for people to accidentally participate.

A vignette: last month my partner was booking a private corporate dinner and got a spreadsheet from a coworker with contact info for several potential restaurants. After 45 frustrating minutes of bounced emails and unanswered calls, she finally asked what was going on. A bit of sleuthing revealed the issue: her coworker had asked AI to generate the list, since neither of them lived in the city of the event, and passed it on to her. The restaurants were real, but every phone number and email address was hallucinated.

AI is full of these potential gambles. Would you risk wasting an unknown amount of a coworker’s time to save 15 minutes for yourself? What looks like an efficiency at a personal scale may net out as time lost for the team.

I once heard that space travel is brutal on the body. In zero gravity, the body begins to “forget” the constant pull it was built to resist, and adapts in ways that make it worse at living on Earth. Muscles waste away, bones lose density, and the heart weakens because it no longer needs to pump against gravity. Even the eyes change shape and vision gets distorted. Life on the space shuttle makes the body and mind forget what real life on Earth feels like.

I’ve always thought this was a fitting metaphor for extreme wealth. Too much money dissolves the resistance of reality, suspending a person in a kind of psychic zero gravity—an atmosphere of yes-men, sycophants, and transactions. Over time, that absence of friction warps perception, and behavior grows more extreme, as if trying to provoke reality into responding. What’s emerging with AI-induced psychosis feels similar: a sycophantic companion lures you into an addictive sense that reality is optional, until you are overwhelmed by the creeping mania embedded in the simulation that comes from living without resistance.

I’ve given a few corporate talks over the past few months, and one of the suggested talking points was to reassure employees about job displacement in the face of AI. For the most part, I refused to sugar coat anything. Reassurances need to come from people inside the company with influence and power, not outsiders with a slide deck and a plane ticket home.

One of the common lines you hear is: “AI frees you to do the human work.” That’s a load of bull. That kind of work was always available before AI, and if it wasn’t valued then, why would an organization value it now? Why do we need AI to take away the minutiae before we start appreciating what people can offer? If the busywork is so overwhelming that it prevents more meaningful contributions, that’s not a technology problem, it’s bad management. And if that’s the case, maybe the AI should replace the managers, not the workers? The whole line of reasoning is absurd.

One of our key mistakes, I think, is treating labor displacement as a problem of technological capability, when it’s really a reflection of leadership’s values and incentives. What the hell do we do about that? Moloch, oh, Moloch!

I didn’t talk much about coding beyond vibe coding, but I think one of the most exciting places to apply LLMs is in an IDE with a code-savvy person piloting it.

Software development has its own “surprising details,” but the work is, at its core, about codifying those surprising exceptions along with the general rules of logic that drive the software. Code is unusually well-suited to these models: its syntax is stable, its reference material is abundant, and its logic is explicit enough that both inputs and outputs are legible to machines. Unlike natural language, code is less ambiguous, more self-contained, and able to be tested, making it a kind of native habitat for large language models to reason, learn, and improve. The important thing, I am told, is to maintain the primacy of programming as theory building.

Creative practice as theory building is such a juicy idea to apply to other domains, but I didn’t have time to get into it. I cut the little bit I had about this, because the talk was already at time, and I’m not a developer. It felt like dangerous territory for me to tread into, highly likely to, what is the phrase? Foot-gun? Rake-step?

These models are mathetimatical phenomena on top of commonly available information. I don’t want to diminish the work necessary to get them to something suitable for use, but to what extent do we believe these technologies have a path foward that isn’t commoditization? I suppose that is the test ahead.

The talk finishes by looking at how the models were able to mimic Miyazaki’s style. To a much smaller extent, the same is true for me. The models have an understanding of Frank Chimero out of the box thanks to a decade of writing on the open web, and part of the work in the last few months has been thinking through how to use that to my advantage.

I ended up in an interesting place, I think. My workflow for this talk was sharing an outline of a section with ChatGPT, then asking it to write it in the style of “Frank Chimero.” This was like looking at your own prose in a funhouse mirror. Do I really use the verb “unfold” that much? Jesus.

From there, I bucked hard against the output, typically starting from scratch. Nothing sharpens your articulation quite like feeling misunderstood. Anger is a powerful fuel. I plan to continue with this dirty fuel for a while.

Building on that, another irony: many of the artists and creators whose work formed the training sets for models are the ones abstaining from using GenAI tools. But, a provocation: who is more entitled to use these models than the people whose work was stolen to train them?

I respect if a creative wants to abstain from using GenAI for aesthetic reasons, lack of interest, environmental, or other moral concerns. But the theft has happened. What now?

What is more American than building an industry from stolen property and labor? Look at this land and its history.

Scribbled in my notebook: peak oil = peak data? What if synthetic data doesn’t work out? Models as time capsules of 2024? Fuzzy, but interesting.

While researching Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst’s work, I came across the metaphor of “centaurs and minotaurs,“ used to describe two opposing postures towards human-AI collaboration. They cover similar territory as Eno’s gardening and cultivation, so I left it out to not muddy things up too much with mixed metaphors.

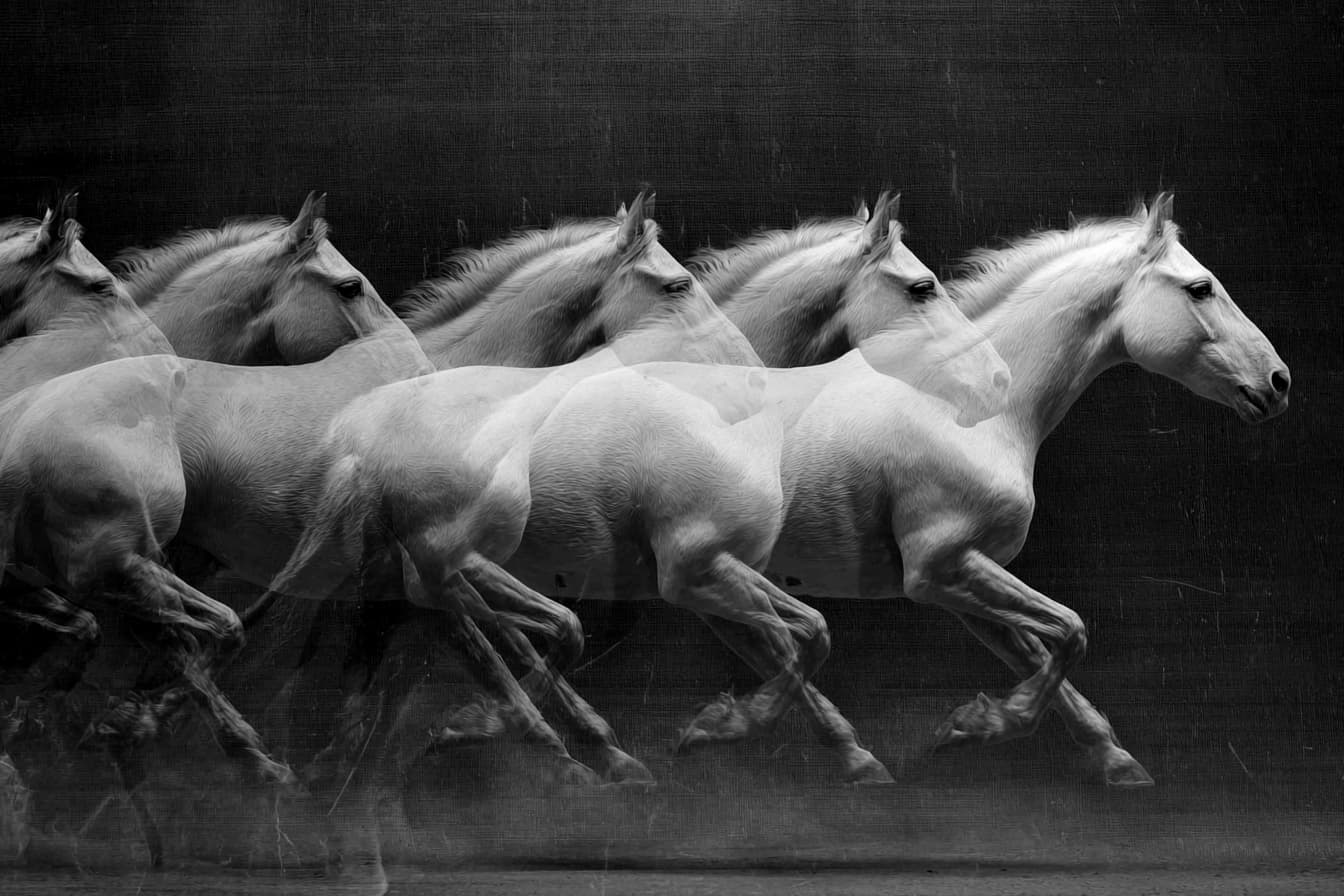

A centaur is a mythical creature with the head and upper body of a man and the lower body of a horse. In the centaur model of collaboration, the human and machine cooperate by the machine executing and the human leading and deciding.

A minotaur, in contrast, is a mythical creature with the body of a man and the head of a bull. In the minotaur model of collaboration, the human and machine cooperate by the machine leading and deciding, with the human executing.

In a sense, both exhibit “human in the loop” qualities, but have very different power dynamics. The Centaur metaphor has existed for quite a while, initially being coined in relation to advanced chess, where a player and a computer team up to face another computer/player team. The computer helps the player think, but the player decides and makes the move.

An aside to the aside here: Brian Christian’s The Most Human Human makes a captivating insight. He says that all the chess grandmasters have the opening and closing playbooks memorized, so all the real chess happens in the middle of the game. It’s an incredibly robust idea, and tantilizing to think about how it could apply to other aspects of work and life.

OK, back to our centaur/minotaur metaphor. The minotaur metaphor seems more recent. I found a 2023 paper on national defense from the US Army War College Quarterly that uses the term. It inverts the centaur model and speculates on manned-unmanned military teams of the future, where teams of humans are under the control, supervision, and command of artificial intelligence. Many of the minotaur examples I could find are predicated on speed of response and the application of force.

Cue the quote from that ’70s IBM presentation: “A computer can never be held accountable, therefore a computer must never make a management decision.”

What about war?

Another cut: does agentic AI even make sense for consumers? I am tired of seeing grocery shopping demos. Most of the things we want agents to do are made purposefully difficult by the counterparties (booking travel at optimal cost, renegotiating credit card interest rates, syncing data across siloed software, cancelling your New York Times subscription, etc.). When we say we want an agent to do something for us, it typically is a wish for greater consumer protections. We don’t need an agent, we need better legislation.

One of the strangest moments in researching the talk was watching this interview between Rick Rubin and the founders of venture capital firm a16z. It’s an unlikely bunch. The whole conversation is fascinating—it’s like watching extrinsic motivation personified talk to intrinsic motivation personified.

One of the consistent beats in Rubin’s creative worldview is that inspiration comes first and the audience comes last. The spark that compels an artist to create must lead. In his book, Rubin argues that if you begin by thinking “How will this be received?” or “What will people want?”, you’re already limiting your work, because the audience only knows what’s come before.

This is, of course, anathema to the VC tech world, where implementing user feedback is seen as driving a company towards product-market fit. The cues and direction come from the outside, to the extent that Y Combinator, another fund, has inscribed it in a frequently shared credo, “Make something people want.” (Which I presume gets lost in the shuffle when you receive funding?)

What makes the Rubin conversation so compelling is how oblivious the investors seem to the gap between their worldview and his. They fill the hour with anecdotes and external references, never quite grasping the possibility that a person might make something because they feel an inner need to—there’s something inside them that wants out—and that not all meaningful work requires an external validation like money or market traction.

It reminds me a bit of a conversation at Config last year where Figma CEO Dylan Field was stunned that Jesper Kouthoofd, CEO and founder of Teenage Engineering, didn’t user test his instruments before releasing them.

I think part of the dismay and boredom with technology these days comes down to how few products (software or hardware) seem to have a coherent point of view. In fact, success aside, I think that’s part of what we miss most about the Jobs-era of Apple. There was a sense of vision and authorship rather than inevitability, and a focus that extended beyond incrementalism and scale. There were hits and misses, iPhones and cube computers, iPods and iPod socks.

For some types of work, it’s better to navigate by one’s own internal sense of rightness rather than by external signals. We tend to call this “vision,” but that word has been evicted of meaning these days, more often suggesting one’s ability to predict consensus instead of their ability to create from conviction. I believe the malaise surrounding tech over the past decade, for both workers and consumers, stems from its gradual shift away from being a creative industry.

Real creative work begins from the inside. It is an act of contribution, not competition. One instrument doesn’t cancel out the others, one album doesn’t erase the last. Rubin and Kouthoofd both seem to understand that creation is additive, not adversarial, and the adoption of AI seems to suggest that each model and tool doesn’t necessarily cancel out the necessity of the other ones. I know many people who subscribe to both ChatGPT and Claude and use them for different jobs. Each model and version of each model offers something a bit different. It’s another reason why I’m keen on comparing AI to an instrument.

Perhaps the technology industry might be a more genuinely innovative place if we could eschew the tools, the hype, and the money for a moment and actually listen to what is stirring inside of us. If AI really can democratize the production of software, than what could be better than having a multiplity of options available, all with a sense of authorship and a unique touch? If there is one thing I strongly agree with Rubin on, it is this: the future begins by feeling it.

There is a wonderful line from As You Like It, where Orlando says, “I can live no longer by thinking.”

I just discovered it, but wish I found it earlier. It would have been nice in the talk.